After a few extra days in the seaside town of McMurdo Station, we flew on a ski-equipped LC-130 for the sunny environs of South Pole Station, where we had a flawless touchdown on the groomed skiway next to the station. This is our last stop before embarking on the traverse in about a week. Our main objective here is to prepare our vehicles and sleds for travel, and take some cool pictures.

The team at the bottom of the world.

The Amundsen-Scott South Pole station is located right at 90 degrees south latitude (ok, maybe not exactly there, but the station is within about 100m of 90 S). It’s named for the Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen, who first set foot here in December of 1911, and for the British explorer Robert F. Scott, who followed closely behind in January 1912. The United States established a station here in 1957 as part of the International Geophysical Year, and it has been continuously occupied ever since. The current station, commissioned in 2008, is the third major station the U.S. Antarctic Program has built here. The prior station (the iconic geodesic dome) was disassembled and sent back to the US.

The elevated design of the station is intended to reduce snow drift, a major consideration when building structures on the ice sheet.

We are here in the height of the summer season, and there are ~150 people on station making the most of the relatively warm weather (-30 C, or -22F) for construction projects, moving cargo, and of course, science projects like ours. In winter, the station is much quieter with around 40 people spending the long winter keeping the station running.

For the first few days we’re here, our main job is to do very little. The South Pole Station sits on top of the East Antarctic Ice Sheet at about 10,000 feet above sea level, which is a big jump from the sea level McMurdo Station. The keys to acclimatization are to drink plenty of water and avoid exercise, though a little walking is fine. After about three days, we will be cleared to move on to more vigorous activities.

The 2017 geographic south pole marker.

There is a marker placed at the geographic South Pole, designed by the wintering crew at the station. Every year on January 1, the new marker is placed and the marker from the past year is put on display inside the station. Since the entire station (and skiway, and cargo, and traverse vehicles) are on top of the ice sheet, the whole station moves along with the ice. The ice shifts about 30 feet per year toward the 40 degrees west line of longitude where it eventually becomes part of the Filchner-Ronne ice shelf. (Don’t worry though, at the current velocity, it will take tens of thousands of years to get there.)

The perhaps more familiar scene is from the ceremonial south pole – a post with barbershop stripes and a reflective ball on top, surrounded by the flags of nations signing the original Antarctic treaty. The two poles are a few hundred yards apart and are both worth a visit if you find yourself down this way. Tell ‘em Tom sent you.

The team at the geographic south pole: Forrest McCarthy, Tom Neumann, Kelly Brunt, and Chad Seay.

Earlier today, we visited our cargo that we shipped from McMurdo and had a look at our sleds. It looks like everything has arrived, and as soon as our breath catches up with us, we will begin packing the sleds and pitching our tents!

-Tom and Kelly

Tom and I arrived in McMurdo Station, Antarctica, last Tuesday. Since then, it has been a busy week, full of specialized training and preparing to depart into the deep field…

We flew from Christchurch to McMurdo – 7.5 hours on a C-130 airplane operated by the Royal New Zealand Air Force. There were 38 passengers in the front of the aircraft and three pallets of gear in the rear. The passenger space is extremely tight; you have to work together with your neighbors to share space in an effort to remain as comfortable as possible for the long flight. And ladies, the restroom facilities are not fabulous.

Kelly and Tom on the ice runway at McMurdo Station, Antarctica (Credit: Neumann)

We landed in McMurdo on one of the nicest days that we’ve seen. It was about 25 F and sunny. Folks that had been down here before were excited to be off of the plane. And folks that had never been here before were in awe, and just wandered around on the ice tarmac, taking it all in.

The view from the runway is quite spectacular. You are standing on an ice shelf, or the edge of the ice sheet that has met a bay and is now freely floating on the ocean. In one direction, you see the full Royal Society Range and the McMurdo Dry Valleys, one of the few places on the continent where rocks are exposed through the ice. In the other direction, you see Mt Erebus, Earth’s southernmost active volcano.

Tom and Kelly at the McMurdo Station sign (Photo: Brunt)

From there, we got in a massive vehicle called Ivan the Terra Bus and headed to McMurdo Station. The driver, Shuttle Bob, is quite possibly the best greeter for any station anywhere. The ride to the station was about 15 miles and took us a little under an hour, as we moved slowly over the ice shelf. Once on station, we were given keys to our rooms, ate dinner, and went to bed. The real work started quickly the following day…

The next few days were completely full of specialized training, including tips and tricks for safe deep-field camping, altitude training, and environmental briefings, where you are reminded just how fragile this environment truly is. We have also recently received training on how to drive the PistenBullys, which are the vehicles we will be using for our traverse. These are tracked vehicles that are more commonly seen grooming ski areas in North America.

Tom and Kelly inside a PistenBully, like the one they’ll use for the traverse along 88 degrees south.

(Photo: Brunt)

Along with training, we spent a lot of time this week grabbing deep-field gear and then packing our cargo to fly to the South Pole, where we will depart on the traverse. Our cargo includes science instrumentation, vehicle parts and tools, food, and camping gear, such as tents and sleeping bags rated to -40 F. And our cargo also includes some creature comforts, such as skis and ukuleles.

Tom banding up our last bit of cargo to enter the system — this precious box contains the coffee for the traverse. (credit: Brunt)

And finally, the week has included a never-ending pursuit for a good cup of coffee. The coffee in the galley consists of ground beans that come from a can. While we did bring coffee south with us for the traverse, those beans are already in the cargo system, ready to go to the South Pole. And there isn’t a Starbucks or Dunkin Donuts anywhere to be seen. So, we found the next best thing: The McMurdo Coffee House. A team of baristas, who are officially down here with other jobs, step up to the plate and provide the community with the best coffee available on station. They work exclusively for tips and often receive cash, fresh fruit, and even mission stickers (which are somewhat like currency down here).

The McMurdo Coffee House (Photo: Brunt)

Our flight to the South Pole is scheduled for this Friday, and we are pretty much ready to go! So hopefully, next week, we will be blogging from Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station. Stay tuned!

-Kelly & Tom

Greetings from New Zealand!

Soon, we’ll report back from even further south. We’re headed to the heart of the Antarctic ice sheet, to collect measurements on the ground for the ICESat-2 mission.

While NSF calls us the 88S project, sometimes you need that extra precision. We’re NASA. (Logo design by Adriana Manrique/NASA)

ICESat-2 is a NASA satellite, scheduled for launch in 2018, that will measure the height of ice sheets, glaciers, and sea ice in unprecedented detail. Designed and built at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center, it will carry a laser instrument called the Advanced Topographic Laser Altimetry System (ATLAS). ATLAS will send out small pulses of laser light, and precisely time how long the light takes to travel from the instrument, down to the earth, and back. These measurements, along with the position of ICESat-2 in its orbit, and the direction ATLAS was pointing, allow us to determine the height of Earth’s surface wherever ICESat-2 goes.

But how do we know those measurements from space are correct? We take a sample of measurements on the ground, which we can check against data gathered by the satellite. Which leads us to Antarctica.

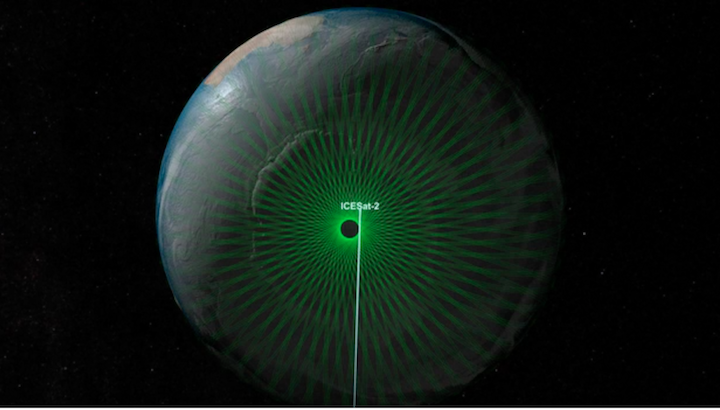

The green lines trace the path where data will be collected by the ICESat-2 mission. The tracks come closest to the poles at 88 degrees north and south, forming a dense network of crossing tracks. (NASA’s Scientific Visualization Studio)

Due to the particular orbit of ICESat-2, all the tracks for the satellite converge right around a latitude of 88 degrees south. Our plan is to travel to 88S and collect measurements of the ice sheet elevation around part of the circle at that latitude. We will compare our measurements with those from ICESat-2 shortly after launch to evaluate the performance of the satellite.

Kelly and I left the US last week after months of preparation, and are now en route! The first stop on our journey is Christchurch, New Zealand, where we recalibrate our internal clocks, collect the last of our cold-weather gear, and smell the roses before heading farther south. We are traveling along with science investigators and support staff working through the Antarctic Program of the US National Science Foundation. Christchurch has been the launching point for US (and New Zealand) field work in the Antarctic for decades, and we are grateful for the support of the NSF and our colleagues here in New Zealand. It is a huge advantage to follow in the footsteps of the thousands of other Antarctic program members who have gone before us.

An array of hats, jackets, and gloves are available at the Clothing Distribution Center in Christchurch NZ to keep us warm while we’re down “on the ice.”

As you might imagine, it’ll be cold where we are headed, and having the right clothing is critical. Today, we visited the Clothing Distribution Center to borrow gloves, hats, parkas, and other items to keep us warm and safe. Tomorrow morning, bright and early, we’ll return to the CDC, get kitted up, and head south for McMurdo Station, the U.S. hub of operations in Antarctica.

Fingers crossed, and we’ll report next from Antarctica!

-Tom Neumann and Kelly Brunt

Perhaps you know the feeling: that moment when you see with your eyes something you have previously only seen in pictures. Before today, I knew the Larsen C ice shelf only from the satellite images we have published since August 2016. The attention paid to the shelf off the Antarctic Peninsula has been due to a rift that eventually calved an enormous iceberg. Today (November 12), the Operation IceBridge mission flew its suite of airborne instruments over the shelf and I caught a first-hand look.

The view from the P-3 after take off shows mountains that received an overnight dusting of snow in Ushuaia, Argentina. Photo by Aaron Wells.

I was aware that I would be seeing an iceberg the size of Delaware, but I wasn’t prepared for how that would look from the air. Most icebergs I have seen appear relatively small and blocky, and the entire part of the berg that rises above the ocean surface is visible at once. Not this berg. A-68 is so expansive it appears if it were still part of the ice shelf. But if you look far into the distance you can see a thin line of water between the iceberg and where the new front of the shelf begins. A small part of the flight today took us down the front of iceberg A-68, its towering edge reflecting in the dark Weddell Sea.

The edge of A-68, the iceberg the calved from the Larsen C ice shelf. Photo by NASA/Nathan Kurtz.

This particular flight, however, aimed to get more than just a surficial look at Larsen C; to understand the system as a whole, scientists also want to know the bathymetry of the bedrock below. To do that, the flight path was planned with gravity measurements in mind. While radar instruments can “see” through snow and ice on land to map the bedrock, radar has trouble when instead of land there is water below the ice. For the gravimeter, that’s not a problem. The new flight lines—flown for the first time—followed the ground tracks of the future ICESat-2 satellite, and simultaneously increased the area of Larsen C mapped with the gravimeter.

John Sonntag, Operation IceBridge mission scientist, takes notes during the science flight over Larsen C. The planned flight lines are in the foreground.

Nathan Kurtz (IceBridge project scientist) and Sebastián Marinsek (Instituto Antártica Argentino) observe Larsen C from a window on the P-3.

Credit: NASA/Christine Dow

By Christine Dow

We have arrived back safe and sound after 11 days crossing the Southern Ocean. Our exit from Jang Bogo involved one last (very short) helicopter ride taking us to the Araon icebreaker so that they didn’t have to re-break ice to get back into port. I stayed up till the wee hours on the top deck watching us motoring away from my home for the last month, pushing large chunks of sea ice out the way. Some Adélie penguins were also witness to our departure along with snow and cape petrels diving and swooping around the wave tops. It was a very idyllic sight and I was sad to say goodbye to the Antarctic (until next time).

Credit: NASA/Christine Dow

Onward ho. Over the next few days we crashed and bumped our way through the sea ice. This was a good chance to get used to the (very) rolly motion of the boat. Icebreakers are designed with highly rounded keels, excellent for smashing through ice packs but not so great on the stomach. A very good distraction was the on-board table tennis table. Many doubles games were played over the course of the voyage, some more successful than others depending on whether the boat allowed both balls and players to be on a sensible trajectory.

Credit: NASA/Christine Dow

After two days, we were almost out of the sea ice pack when we suddenly had to turn around and return south. There had been a distress call from a fishing boat stuck in the ice and R/V Araon went to the rescue. We successfully hauled the boat free from the ice that it had become wedged on and escorted them to a region easier to navigate through. On the return journey we also stopped to collect some long sediment cores that the Korean scientists will analyze later.

The timing of our journey meant that we had Christmas on board the boat. Our party was on Christmas Eve and involved a veritable feast – the chefs had been very busy all day kindly preparing this for us. One of the Korean scientists also played some clarinet and saxophone music to get us in the Christmassy mood. We even had a Christmas tree, lashed to a railing to stop it flying all over the place.

Credit: NASA/Christine Dow

On the 11th day of our journey we could see land. It was very strange to see trees and green again after so long with just hues of blue and white. We had also been slowly getting used to the dark as we moved north following our time in 24-hour daylight; the first sunset of the voyage had been spectacular with giant albatross swooping behind the boat. I watched as we finally docked at the port of Lyttleton in New Zealand, feeling that “normal” life would be a little surreal after our adventure. It was time to say goodbye to our friends and colleagues and go home, just in time for the New Year. After such a trip it’s not surprising that one of my resolutions for the new year is to get back to the frozen continent…some day.