By Lora Koenig

Byrd Station (Antarctica), 11 December — We all got up at 5 AM this morning. I had gone to bed at 2 am because I had been backing up all of the radar data, which took much longer than anticipated. The traverse team went to bed early to be rested for the day.

It was a beautiful morning: warm, no wind, with thin, low, overcast clouds. The sleds were loaded and ready to go, already hooked on to the snowmobiles. Ludo was the first to the sleds and he started the generator, which powers heating pads that are used to warm the radars after being cold soaked all night. After about 15 minutes of warming, the radars can be started. During this time, the GPS is also turned on so it can obtain lock with the satellites and provide accurate positions.

I took the snowmobile covers off and helped Michelle load the final sleep kits on the sleds. The sleep kits are the last things to be loaded and contain a sleeping bag, sleeping bag liner, insolite pad, thermorest, pillow (if you want one, though most of us prefer to just use big red as a pillow), and a pee bottle so you don’t have to leave the tent in the middle of a cold night or storm. All of this is stuffed into a duffle bag and goes with you everywhere inAntarctica.

Once the generator was started, the team headed into the galley for a quick breakfast. Most of the camp was still asleep because Sunday is their day off; however, Kaija and Tony, the camp manager and assistant manager, came up to see the team off. After breakfast, the radars were turned on and the snowmobiles started. We took some final pictures and I tried to shoot some video but the small video camera we brought along is not operating well in the cold. The feeling of both excitement and nervousness was in the air. Excitement for finally getting to the traverse portion of the science and nervousness because the team is headed out into the remoteness ofAntarcticaalone. They will no longer have the security of an established camp and will have to rely on each other for everything. The team is strong and I know they will do well. During the traverse they will most certainly cover ground that no human has ever walked on before.

At 6:41 AM, Michelle led the team out of Byrd Camp. She pulled a Siglin sled and a Nansen sled with food, the Scott tent, an HF radio for emergency communication, the radar spare parts, the sleep kits and personal gear. Michelle rides one of the two snowmobiles with mirrors so she can easily watch the team. Jessica followed pulling 2 Siglin sleds with food, the ice core drill and two ice core boxes. Randy was third in line with two Siglin sleds with even more food, the mountain tents, emergency bag, and all of the fuel. Ludo pulled the final snowmobile out and into line pulling the radar sled with Clem on the sled operating the radar. We all screamed and waved as they pulled away.

I continued to watch as they moved further towards the horizon. They became smaller and smaller dots on the horizon above tent city as they moved away from camp. At 7:12 AM their dots blurred into the horizon. The traverse had begun.

They will travel 95 km (59 mi) today, their longest stretch of the entire traverse, to the first camp site. They are moving toward higher snow accumulation and towards WAIS Divide field camp. When they reach the site tonight, they will be95 km(59 mi) from Byrd and85 km(52.8 mi) from WAIS Divide, so if they have any problems they will head to WAIS Divide, not Byrd.

I am feeling very lonely sitting in Byrd camp without the team, but there is still important work to do. Remember, the team still does not have their fuel caches. The pilots are in camp, but today’s overcast weather, while great for traversing, is not adequate for flying: The clouds make it difficult to see the snow surface. The pilots call this surface definition. In order to do open field landings (landings not on a ski way), the pilots cannot have overcast clouds at any level. Now I am just waiting for the weather to clear so that the plane can cache the team’s fuel and ice core boxes. I am also waiting for an LC-130 to come into Byrd so I can get a ride back to McMurdo and then back to the U.S.

Today I will also check the base station GPS and give a science lecture about our traverse to the Byrd Camp residents.

Everyone at Byrd Camp has helped us so we can complete our science goals and it is much appreciated. Thank you, Byrd Camp! We especially enjoyed the wonderful food made by Chef Rob. The team’s send-off dinner was duck with a port sauce, chicken with polenta, pureed carrots, broccoli with hollandaise sauce, and Boston Cream and Lemon Meringue pie for dessert. Yummmmm!

Around 7 PM tonight I expect to get a satellite phone call from Michelle. From this point on, the blog will have less pictures for a while because we will only have voice communication with the team. It should take between 24 and 30 days to complete the traverse, including (bad) weather days. The team will communicate back to me at each camp site and I will update you on their progress. When they return, we will post more posts from them with pictures of the traverse.

The team is truly out in the wilderness. The only communication they have is through the sat phone, which will only be on for a few hours in the evening. They can call their families and their families can send 160 character text messages to the sat phone. The deep field ofAntarcticais a remote place.

Go team, go!!!!!! (The extra exclamation points are for Clem, who loves to use them.)

Today, Clem and Ludo did a little science. They dragged the radar in a grid pattern around the ice core site from yesterday. This is important data because it tells us how representative the point where the ice core was drilled is of the larger area around it. When we compare ice core data to satellite data, we want to know if the larger area is homogeneous (similar) or not.

Randy made sure all the snowmobiles were ready and fueled to leave early in the morning. One of the choke leavers on a snowmobile broke off so he was working with the mechanic to get it fixed. Jessica looked at the electrical conductivity measurements from yesterday and took pictures of all of the log book pages to create a back up of the data. Michelle spent the day making sure all the gear was loaded well on the sled and that nothing was missing.

I spent most of the day watching the weather and talking with pilots. We cannot carry all of our gear on the sleds. A DC-3 Bassler aircraft is supposed to drop our fuel and ice core boxes and each camp site before the traverse. Due to the bad weather, the fuel cache has not yet been cached. So I have been talking with the pilots and rearranging the caches so the team can start out and not incur more delays. For now, the team will leave in the morning carrying two ice core boxes and one 55-gallon drum of fuel. This will allow them to get to the first camp site and drill. It will also give them enough fuel to get back to an established field camp if for some reason they don’t get any more fuel. They will not go to Camp 2 until they know the cache of fuel is there. Hopefully the cache will occur tomorrow or the next day so the traverse team will not be delayed.

Everyone will go to sleep early tonight. Because all of Antarctica operates on McMurdo time, the time of the day at Byrd does not match the daily temperature changes. The coldest part of the day, which would generally fall from 1 to 4 AM, is usually between 6 and 10 PM our time. The warmest time falls in the morning between 6 and 10 AM. Tomorrow the team will get up at 5 AM and leave around 6 AM to take advantage of the warmest part of the day. By 6 PM they hope to be cooking dinner and in their warm tents.

By Lora Koenig

Byrd Station (Antarctica), 9 December — Today was a huge day. First off we figured out the problem with the radars: One of the USB ports on the computer was not functioning properly. When we changed the USB port, the problem went away. I was relieved there was such a simple solution to the problem and so was Clem, who had had a rough night’s sleep worrying about the radars.

At around 9 AM we headed out to drill our first ice core of the season. We drilled at a site about 3 kilometers (1.86 miles) away from camp. This site was chosen because a previous ITASE core was drilled there in 2002. Our core will update this core and we will compare the overlapping years of ours with ITASE’s to understand any differences. Last year we also drilled at a site of a previous ITASE ice core and got similar results that give confidence in the measurements and methods from both cores.

Clem ran the radar out to the drill site to image the layering while Ludo drove the snowmobile. Once at the site, Ludo immediately started digging the snow pit to sample the snow in the top 2 meters (6.56 feet) of the ice sheet. The snow at the very surface of the ice sheet is very similar to the hard wind-packed snow that you would encounter in the high mountains in the U.S. and it’s not bonded well enough for us to ship cores of it back to the U.S. in one piece, so instead we took samples of the snow in the pit for lab analysis. The cores have to stay in one piece, or we would lose our chronological record. Additionally, we took other measurements in the snow pit that are important for modeling how the microwave radiation, from both the satellites in space and radars on the ground, interacts. Snow grains of different sizes and shape can actually be detected by satellites in space! As the snow grain size changes, the signals in space change.

Ludo spent all day in the pit. We think he may hold the record for the most time in one pit, about nine hours from digging to fill in. He took infrared photographs of the snow. Here is one from the pit:

These photographs are used to calculate the grain size given the different reflectance levels of the infrared radiation. The photos are pink because they are taken in the infrared wavelength, not visible light like most cameras do. They are also very pretty to look at and you can see all of the layers of snow. Each storm puts down a new layer of snow. There was a new layer approximately every 6 cm (2.36 in) in this pit. There were more layers than I have ever seen before in a pit, which made the pit measurements take such a long time.

At about a third of the way down the picture the snow becomes firn, which is snow that had persisted through at least one melt season. We cannot tell from the snow pit exactly how old the firn in the pit is (we need the isotopes for that), but we know that there are at least three years of records in the pit, so the firn at the bottom could be from 2009.

After the infrared photos, Ludo recorded the stratigraphy of the pit (snow grain size and type) using a macroscope, cut snow samples for isotopic analysis, and measured the thermal conductivity of the snow, which is the snow’s ability to transfer heat. Heat conducts through the ice lattice more than through the air in the pore spaces, so thermal conductivity is also a measure of how bonded the snow is. Because I was helping Ludo in the pit there are not any photos of this process. Often while we are actually doing the science we don’t have many photos because we are all working.

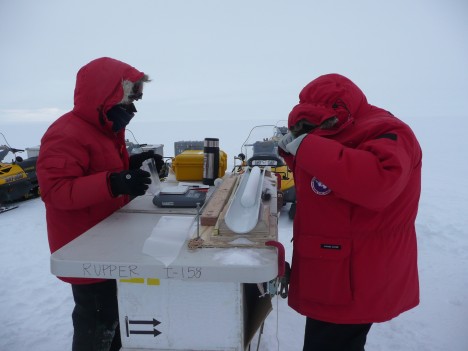

As Ludo was working in the snow pit, Randy started drilling the ice core. He would drill the core and Jessica and Michelle would process it. The core is weighed and measured to calculate its density. The length of the core and the depth of the drill hole are recorded, and the electrical conductivity of the core is measured to detect changes in snow chemistry. The core is then put in a bag, a tube and a box for shipping back to the lab for isotopic analysis. The final depth of the core was 16.8 m (55.1 ft), which will correspond to about 40 years of snow accumulation history.

By Lora Koenig

Byrd Station (Antarctica), 8 December — Today was our first day in the deep field at Byrd Camp. Byrd Camp sits in the middle of the West Antarctic Ice Sheet at an elevation of about 5,700 ft (1,737 m). We are standing on over 2,000 m of ice, with the oldest ice being about 50,000 years old. (The ice nearby at WAIS divide camp is a bit older and deeper. To find out more about the deep ice underneath us check out this information on the WAIS Divide ice core, which is being drilled deep into the ice nearby.) When you look out from camp you see nothing but the flat white snow and an old drill tower sticking out of the ground.

We are, specifically speaking, at Byrd Surface Camp. The original Byrd Camp, established in the 1956-1957 season, is underneath us, except for a drill tower that still sticks out above the snow. Over the years, snow accumulation (which averages around 12 cm per year at Byrd) buried the original camp and created Byrd Surface Camp, which everyone just calls Byrd. It is exactly this snow accumulation that we are here to measure with ice cores and radars. Here is an article about the history of Byrd.

The team was prepared to work hard today because we know the more time we make up from the weather delays, the quicker the traverse team can get home. The day started with all of us breaking down the pallets of gear. Once all the gear was off of the pallets, we divided and conquered the tasks for the day. Michelle started loading and organizing the sleds. Randy fueled all the snowmobiles and Jerry cans. We brought nine 55-gallon drums of premix gas for the snowmobiles for the entire traverse. Jessica prepared all of the drilling gear for the first core, which we’ll drill tomorrow. Clem, Ludo and I built the radar sled, attached the antennas and hooked up all of the radars for testing. Clem also set up a GPS base station that we will use to correct our roving GPS on the radar so we know precisely where the radar data is located throughout the traverse.

We discovered a few problems today. First, Jessica realized that the power converter for the drill battery did not make it to the field. The drill is made in Switzerland and has a different power plug. While this was an unfortunate oversight, it will not affect the science: We can charge the drill battery with the solar panels. The sun is up 24 hours a day here, so that will provide more than enough charge for the battery. Also, we carry an electronics tool kit, so in case of need we can cut the wires and make a new plug.— we call it “MacGyvering” (i.e., improvising fixes to our materials in the field).

The second problem of the day is a bit more worrisome. The Ku-band radar data has a systematic noise level that we cannot troubleshoot. We know that it has something to do with the computer that runs the radars, but we cannot determine whether or not the problem is coming from radio frequency emission from the computer itself getting into the antennas or if it is a data writing problem with the computer software. It has been a long day, so the trouble-shooting will have to be left for tomorrow. We hope that nothing was broken on the computer during the combat off-loading. We will know more tomorrow.

The sleds are ready to drill our first core tomorrow!

By Lora Koenig

Byrd Camp (Antarctica), December 7 — At 4:45 PM today we boarded another Delta for a ride to Pegasus field. The last weather report we had for Byrd Camp was for half-mile visibility and 40-knot winds with blowing snow. The conditions were predicted to continue to deteriorate, so I expected the flight to be canceled. When we arrived Pegasus we saw our gear being loaded on an LC-130 flown by the 109th Air Wing. We also saw a plane taxiing to the skiway that was headed to WAIS Divide camp, which is about 100 kilometers (62 miles) from Byrd. So when we say that plane take off, we knew we had a good chance of getting into Byrd.

We took off at around 8 PM for the 3-hour flight to Byrd. Jessica got to ride in the cockpit for take-off. During the flight, we looked out the windows into clouds for most of the time, but at one point the Ross Ice Shelf was visible and we saw a large crack in the ice shelf, which was exciting to see though I do not know anything about the science behind it. I will ask and expert in a few weeks and get back to you with more information about the crack.

We arrived Byrd Camp around 11:00 PM. After we landed, all of our cargo was combat off-loaded. A combat off-load is when they open the back of the LC-130 and send the palettes out the back with a swift kick and a sudden acceleration of the plane. This method is very rough on our gear and we will have to double-check everything again to make sure nothing is broken. One of my constant reminders to the team is, “Don’t break anything”: We have to fix anything we break and we may not have the parts. So combat off-loading of gear makes me very nervous, but we didn’t have any other choice. And it is actually really fun to see the combat off-loads if you forget that it is your gear.

Here are some pictures of the combat off-load:

Here is a picture of the team finally in the field.

We had a quick tour of Byrd Camp and then went to tent city to our tents to sleep for the night. I was warm all night but others were a bit cold on their first night in their tents. We are finally ready to start the science!