By Clément Miège

Kulusuk, 26 March 2014 — “Opa” is a Greenlandic word for “maybe”, as we learned it this morning while talking to Danish guests at the hotel Kulusuk who have been stuck for a few days due to bad weather.

To give you a little bit of background, the southeastern part of Greenland witnesses the highest precipitation rates of the island, in conjunction with strong winds (either from the ocean or the ice sheet). Often, the weather is unpredictable, especially at this time of year. Therefore, conducting fieldwork in southeast Greenland is a gamble.

Last year, when we experience really great weather in Kulusuk the week before our field work, we did not fully realize how lucky we were to be able to go to the field as scheduled. This year, it has been a different story: we have already gone through two storm systems, and yesterday night a third storm hit us, with a lot of wind and snow. We feel like we are paying the price of last year’s fantastic weather.

That being said, this weather is good to prepare the cargo for our flights to the ice sheet. We spent a good part of Sunday getting the low-frequency radar system ready. We worked on the radar sleds, as well as on the tube that will keep the radar antenna straight when we drag the system on the snow surface.

Ludo and Clem, working on gluing the coupling made to connect the radar antenna tubes. (Credit: Rick Foster.)

On Monday, we went to the village of Kulusuk to buy some supplies (we are currently staying in a hotel that is about a 30-minute walk from the village). On our way to the village, we saw four teams of dog sleds ready to leave for Apusiaajik glacier. The dog sleds are carrying skiers and a week-worth of their base camp materials, so the skiers can enjoy the fresh snow!

We walked around the village to get some nice views of the ocean and the sea ice. As we were walking, Ludo made a local friend! A Greenlandic kid who was a really fun guide and gave us a tour for an hour. At some point, we realized that he was always avoiding the direction of the school!

Rick in front of the broken and refrozen sea ice. Imagine how different it is from the open ocean in the summer, with boats cruising around. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

After that, we went to the store and got some food and a propane tank for our stove on the ice sheet. We found everything we needed and headed back to the hotel. We finished the day at the airport further organizing the science equipment.

Rick works on an extension of the ARGOS antenna mast that we already have installed in the field. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

Tuesday, Ludo and I went back to the airport warehouse and finished organizing the cargo for the helicopter flights. We’ve prepared two distinct: one consists of our camp gear, sleep kits, food, personal gear, and some science equipment. The other (which can arrive later), is composed by the rest of the science gear.

Wednesday has been different, and we thought it would be “fun” to walk you through the steps that we have gone through today in terms of decision-making:

In the morning, Thursday’s flight is still ‘opa’. We are optimist and getting ready to leave, packing personal bags and organizing the last bits of equipment.

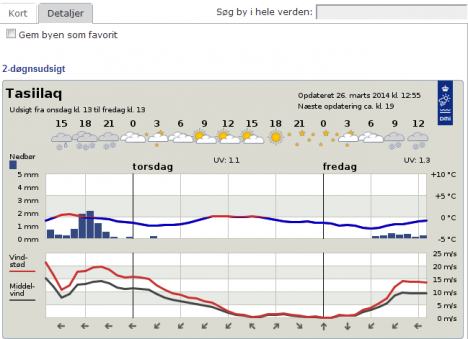

Weather forecast, from the Danish Meteorological Institute, for today Wednesday (March 26) and Thursday (March 27). The good weather window is for Thursday.

2 pm: The weather is not improving much and we start wondering if we will still be able to leave tomorrow. According to the forecast, a break in the storm system is still possible for tomorrow, but we would need it to last for at least a couple of hours, so that we can have one or two helicopter rotations from Kulusuk to our camp on the ice sheet. Each helicopter rotation takes about 2 hours.

3:15 pm: We receive an email from our project manager, based in the US. The helicopter company (Air Greenland) advises us not to leave for the ice sheet tomorrow since an extreme storm is coming for the next days and our team will be incapacitated (meaning that we will not be able to leave the tent for four to six days). This email is worrying us further, and we do not need to be trapped in a tent on the ice sheet without being able to do any work. It is a difficult decision to make, since the weather will be good tomorrow. Moreover, if we leave, we would be able to start working as soon as the storm passed and not be risk further delays in getting to camp, since the helicopter might be needed for other important duties, like resupplying villages. We have to balance the pros and cons — put simply, we have to balance spending four to six days in a tent doing nothing but trying to stay warm vs. gaining about half a day of work, since that way we would not need to wait for our put-in flight. After an intense discussion involving our partners and the weather office, we finally decide that we will not fly tomorrow.

Left: Rick, calling with the satellite phone, using a homemade extended antenna (credit: Ludo). Right: Ludo and Rick waiting to hear back from Air Greenland about tomorrow’s flight. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

4 pm: Our flight for tomorrow is officially canceled.

7 pm: Even if it does not make any sense to have a passenger flight tomorrow due to this upcoming weather system, we think that it will be really valuable to have a cargo flight to drop our equipment. Hence, only one helicopter load will still need to be transported when the storm is over. We’re still working on this option.

We are not sure when we will be flying, but at least we are ready. Please keep your fingers crossed for some good weather. More updates soon, opa!

All the best from snowy Kulusuk!

By Clément Miège

YAY! We made it to Kulusuk on Saturday afternoon! It ended being a not-too-long journey, since all of our flights were on time.

Rick, Ludo and I followed different itineraries. Rick left Salt Lake City on Friday morning and a red-eye flight took him to Keflavik International Airport in Iceland. He landed early Saturday and took a bus from the international airport to the domestic airport in Reykjavik (an hour-long ride).

Ludo came from a meeting in Switzerland and arrived in Iceland late Friday night. He stayed at a nearby hostel in Keflavik. The next day, he was told to take a bus that would take him to the domestic airport and that supposedly departs every hour in the morning. After waiting for a while, with no bus in sight, he walked back to town (carrying 2 duffel bags, a ski bag, and 2 carry-on bags) and learned his first Icelandic words: Saturday and Sunday (laugardaga og sunnudaga.) Turns out, during the weekend, the bus schedule is different. Good thing that taxis were not too far and that he ended up making it on time for his 12:45 pm Greenland flight!

Me, I had a one-day layover in Reykjavik, which was a nice chance to rest a bit and quickly visit the city. I walked around town, not for too long because it was definitely cold and windy and I am not yet acclimated to cold temperatures — but I will be in the next few days!

Reykjavik is a nice city… when it’s not too windy. The day I arrived, the wind was gusting and it was just too cold. But I still went on a walk to check the Hallgrímskirkja church. This is the largest church in Iceland, an amazing structure! Inside, there is a lift, making the church a pretty sweet observation tower with nice views over the city.

[Note: Originally in this post, I erroneously said Halgrímskirja is a cathedral. Thanks to our reader Harry McKone for spotting the mistake!]

On the left, the church with the statue of Icelandic explorer Leif Eriksson. This story explains the first discovery of North America by a Viking expedition, led by Leif Eriksson about 500 years before Columbus: http://www.history.com/news/the-viking-explorer-who-beat-columbus-to-america. On the right, downtown Reykjavik, composed of colorful houses. (Credit: Clément Miège)

The next day, I joined Ludo and Rick at the domestic airport (they both arrived before me). Useless to say that we had a lot of gear between the 3 of us, a total of 6 carry-on bags (including laptops, radar computer, transmitters, GPS, etc.), 5 checked bags (with our cold weather gear), and 2 ski bags. We were a bit scared at first by Air Iceland’s policy of only allowing one 5kg carry-on and a 20kg checked bag per person, but we ended up getting through easily, which was a relief!

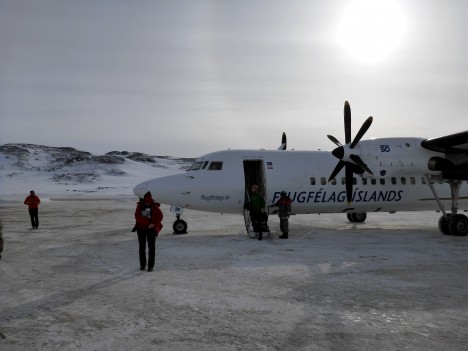

The flight was smooth and fast, only 2 hours to get to Greenland. Approaching Greenland, we started to see more and more winter sea ice along with some big icebergs trapped within it, which is always very pretty. The first islands finally appeared and we were about to land on one of them, where the little town of Kulusuk is.

Interestingly, the sea ice in the fjord next to Kulusuk seemed weaker and it might be thinner this year than when we visited last year. Ludo noticed some spots that were already ice free (see the photo below); those spots were covered by sea ice last April. The wind redistribution of the sea ice and the warm temperature in Kulusuk in January might be the reasons for this weaker sea ice pack.

View from the plane of the sea ice around Kulusuk (the little black dots are houses.) (Credit: Ludovic Brucker)

Our plane, freshly landed at the Kulusuk airport, with a faint sun halo in the background. (Credit: Rick Foster)

Shortly after landing, we made it to our hotel, and started to unpack. This year, Ludo and I brought back country skis, which is a really nice and fun improvement, and also a faster way to get from the hotel to the airport, or to go to the old garage where some equipment is stored from last year.

At the airport warehouse, we found all the equipment that we sent from the U.S. We counted the boxes and, great news, everything had made it her, and was in pretty good shape too! We started to unpack some items and took some of them to the hotel for re-organizing them some more.

At the Kulusuk airport, Ludo moves equipment around to consolidate our cargo (left). Some equipment is ready to be loaded on the helicopter (right) to go to our field site, but other gear needs some repacking, which will be one of our main tasks for the coming days. (Credit: Clément Miège.)

Today, a big storm is here and it’s a white-out outside — crazy, brrrrr! It is snowing horizontally. So happy we are not in the field right now! It is really windy this morning, about 37 mph, so we have decided to work indoors. We have couple projects: preparing antenna tubing for the low-frequency radar, preparing the radar sleds, assembling the ARGOS antenna pole, and starting to pull out the equipment from our last year’s storage place.

I can’t take any photos today, since it’s just white everywhere and impossible to see the surrounding buildings.

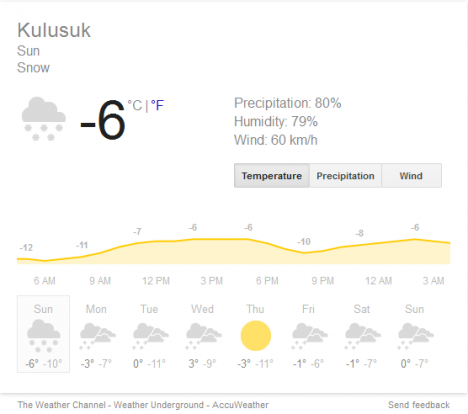

We are still on track for leaving this Thursday (March 27) to go to our camp site on the ice sheet. Amazingly, the only day of the week that looks good for flying out is Thursday — see the forecast below. That is lucky for us!

According to the Weather Channel, the only day with good weather this week is Thursday — good thing we are scheduled to leave then!

I’ll send a new blog post in a few days, stay tuned!

By Clément Miège

Hi there! I am Clément Miège, a Ph.D. student at the University of Utah and I am going to take you along with us to our second expedition to the southeast region of Greenland, to investigate the physical properties of a firn aquifer. And what is a firn aquifer, you might be wondering? It’s a reservoir of perennial water (that is, water that doesn’t freeze in the winter) that is trapped within the compacted snow layer (or firn) of the Greenland ice sheet. If you didn’t follow last year’s edition of this expedition and/or you want to learn more about the firn aquifer, here are some readings I recommend:

We are now getting ready for another expedition to Greenland to further monitor the firn aquifer. This year, our four main tasks will be to maintain our equipment currently in place (which performs temperature measurements), collect additional measurements (with a radar), install a weather station, and try traditional ground-water techniques to date the water and calculate its permeability. I will explain in future blog posts why these measurements are important.

I will be part of a smaller team this year, since only three out of the five members of the first-year team are joining. Rick Forster and I will represent the University of Utah, while Ludovic Brucker comes from NASA Goddard Space Flight Center.

Here is the photo of the team from last year, from left to right; Jay, Ludo, Rick, Lora and I. Lora and Jay won’t be coming to the field this year (we sure will miss them!) If you want to know a bit more about each team member (current and former), you can check this blog post from last year.

Even when we haven’t set a foot in the field yet, the expedition to Greenland started about two months ago with organizing the logistics. Logistics can sometimes be underestimated, but it takes a lot of effort prior to getting to the field to prepare and test the scientific equipment and other field supplies, such as camping gear, food, and power sources.

For this expedition, all of the science equipment (GPS, radars with different frequencies — 5MHz to 400MHz–, piezometers, ice-core drill) was gathered from different institutions in Utah to be packed here and shipped to Kulusuk. Most of the non-perishable food and camping gear was left for over-winter storage after last year’s expedition in a warehouse in Kulusuk, to save on shipping costs.

On March 3 this year, the Utah gear left for Greenland; we’re talking about 800 lbs. of gear that left Salt Lake City on a truck headed to the JFK airport in New York, where it was flown to Reykjavik (Iceland) and then to Kulusuk (Greenland). We got a phone call early this week from our shipping company to confirm that all our equipment made it to Greenland — great news!

Gear packed at the office (left) and ready to leave the shipping facility at the University of Utah (right). We will see this gear again in Greenland!

These last days have been really busy, gathering the last items for our science research, and also personal equipment. Yesterday, I was working at Blue System Integration in Vancouver, BC with a colleague, Laurent Mingo, who is developing IceRadar, an ice-penetrating radar system for the scientific community (see this website for additional info). Laurent has been working on an experimental beta version of the current radar that will allow us to penetrate through the firn aquifer to try to image the bottom of the aquifer gradually transitioning from water-saturated firn to ice.

Even if most of the scientific equipment is already shipped, there are always some last-minute important items that we end up adding into our suitcases (like the low-frequency radar). As a brief anecdote, last year, Rick traveled with a pelican case as a checked bag – inside, there was a bunch of wires hooked up to a datalogger. We were aware that it looked kind of suspicious, so it was a bit scary to go through customs with it! Me, I traveled with a 60-meter long thermistor string weighing over 50 lbs. in my checked bag, because the fabrication and calibration took longer than expected and we weren’t able to ship it ahead of time with the rest of the equipment. This year, luckily, most of the heavy equipment was ready on time and we are carrying only a couple random items in our checked bags.

We are starting our journey this week, leaving the U.S. on Thursday evening for Reykjavik, the capital of Iceland. After a day in Reykjavik, we will leave mid-Saturday on a 2-hour short flight that will take us to Kulusuk, Greenland. We are hoping for good weather; last year, Ludo and I “boomeranged” on our first try due to poor visibility at the Kulusuk runway.

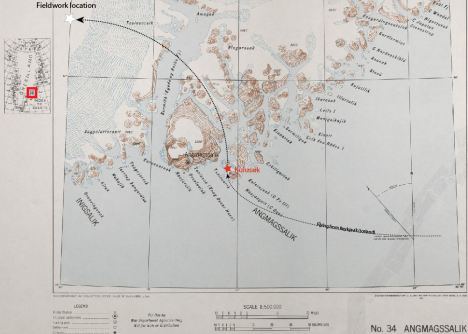

In this old map from the US army (from 1941) you can see the location of the small city of Kulusuk in Southeast Greenland (red star), just below the Arctic Circle (~66.5°N). Our field camp on the ice sheet is represented by a white star. The map can be found at the Polar Geospatial Center.

Kulusuk is our first stop in Greenland. We will be staying at this small village for a few days in order to re-pack our field gear, test that everything is working well (stoves, generators, tents, science equipment, etc.) before going to the field. If we are lucky, we might see one of the polar bears that sometimes come close to town in this time of year.

Colorful houses make up the town of Kulusuk in Southeast Greenland. The shores of the fjord are covered by sea ice in the winter.

After a couple of days, we will be heading to our fieldwork location on the ice sheet. A helicopter from Air Greenland will drop us and our cargo at our study site; it will be an about 45-minute commute.

That is it for this introduction; our next blog post will be from Greenland!

All the best,

Clément

By Clément Miège

Hi there! Today I have another story to share with you! It’s about the tracking of the temperature evolution of the firn aquifer temperature by using two thermistor strings that we set up in the two holes made by Jay (see Jay’s post on drilling for details).

By tracking temperatures over a year, we will observe the firn heating mechanisms in the summer with the melt from the surface of the ice followed by water infiltration in the firn. In the winter, we will get a sense of the refreezing processes from the cold surface air, which cools the upper part of the firn and we will observe the persistence of the firn aquifer over the years.

To achieve this, we installed two thermistor strings with two different lengths: 30 and 60 meters. The shorter string has 60 sensors on it, sampling every half-meter. The longer one will only get a temperature reading every 2.5 meters but it will record deeper temperatures. Both strings are set to collect data every hour for an entire year, assuming the batteries last that long (hopefully!) The temperature chain is called a thermistor string because each sensor is a thermistor, a type of resistor sensitive to temperature changes. After measuring a resistance change, calibration curves allow us to retrieve temperature changes.

The thermistor-string story started in Utah, when we received the equipment late from the manufacturers, giving us only 5 days to work on it before leaving for Greenland. We realized that integrating the whole system together with the satellite uplink would take most of our last prep days.

It was definitely too late to ship the thermistor equipment with the rest of our gear, so Rick and I traveled with it in our checked luggage! I ended up with a 50 lbs of spool coiled with about 60 meters of cable in a suitcase. Rick had a black pelican case as his checked bag, with the second thermistor string, datalogger, ARGOS antenna and other pieces of hardware. We learned how to travel light, bringing minimal clothing, and wearing the cold-weather clothes in the airplane so we were able to meet the airline luggage restrictions – it definitely made for fun travels!

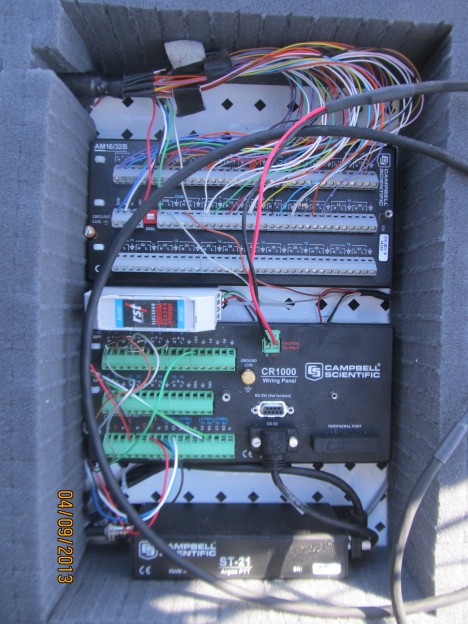

At the Kulusuk Hotel, in southeast Greenland, we finished integrating the thermistor string, mostly by picking the right data-transmission rate to the satellite in regards to our battery consumption estimates. Having the ARGOS satellite uplink will let us receive temperature data via email every day from the field site and tell us almost in real time what the temperatures are in the two holes.

In the field, shortly after drilling each hole (to avoid water refreezing due to cold air down the hole), we lowered the thermistor string down and backfilled the hole with surface snow. Then, we used the Felics drill to make a 4-meter hole to anchor the long pole that holds the ARGOS antenna.

On that day, the 20-knot katabic winds were blowing a lot of snow, so we used a mountain tent as a snow-proof environment to work with the electronics before dropping off the case in its hole. To give you a taste of the wind speed: Rick was charging one of the thermistor-string battery and the wind was so strong that it blew the small 1kw generator off…. crazy! When the winds finally died down, we buried the case in a 2-meter deep snow pit, because we wanted to prevent the case from being exposed to surface densification and melt during the summer.

Last check on the electronics, to make sure all the wires are tightened before closing the box — next opening in one year!

After backfilling the snow pit, the only evidence at the surface of the temperature strings is the top of the pole with the ARGOS antenna and a red flag!

We are hoping to recover the case with the datalogger next year, but we are not sure if the ARGOS antenna will still be sticking out, because this sector of the ice sheet is getting a lot of snow accumulation in the winter. We will use a metal detector to find the metal pipes left near the case.

Because this is likely my last post for this expedition’s blog, I would like to thank the all team for this great adventure and everybody that was supporting this exciting research. Until next time!

By Lora Koenig

Well, I am back in Greenbelt, Maryland, typing with warm fingers in a climate-controlled office with high-speed Internet and drinking fountain just down the hall. After fieldwork, I am always thankful for things I generally take for granted, like being able to charge my laptop by simply plugging it into an outlet. There is no longer a need fill a generator with gas and then start it just to charge batteries. Aw, the comforts of home! (We all had safe trips back to the US and have returned to our home institutions last week.)

For the last blog post of the season, I decided to pull together a few of my favorite photos from our trip to give you a sampling of the great fun we get to have while doing this kind of research. The most fun I had during this trip was on our final day in Kulusuk: we were invited to the Kulusuk School to with the children in the upper grades (who speak some English) about our work. I regret that we do not have any pictures of this event, but we were giving our presentation and letting the students run our small ice core drill, thus neglecting picture taking. The school in Kulusuk has about 70 students and includes all grades. The building has lots of windows and is very bright inside — it is one of the prettiest schools I have been in, with lots of open space, a small kitchen, library and a gym. I especially liked the entrance to the school, which was equipped with plenty of coat hangers and boot racks for the students to shed their cold weather gear as soon as they come inside. Though we were there talking about science, the school in Kulusuk is known for their art. We were hosted by the art teacher, Anne-Mette Holm, and after our talk got to attend one of her classes where the students were making wooden sculptures. We also got to see other student projects including weaving, toy making and furniture making. Quite a portfolio! The students’ art has traveled the world, being shown at different expeditions across the Arctic. (Check out pages 11 -15 of this document for some examples of the children’s art work under Anne-Mette’s tutelage.)

While our visit to the school was definitely the top highlight of the trip here are a few others highlights in pictures.

Seeing mountains from our campsite on the ice sheet, a nice change from the typical flat white ice sheet.

So those were some of the highlights of the field work and now it is time to work with the data we gathered. In the week we have been back, we have already started to analyze our data. We see that, as expected, the densities in the firn (aged snow) above the aquifer are higher than expected and that there is more water than originally predicted. We still need more data to fully understand what this water trapped in the Greenland ice sheet means for sea level rise. We need many years of data to understand how and if the aquifer is changing with time… but remember this was an exploratory mission. When we set out, we were not even sure if our drills would even work. There was a chance they would have just frozen in place and we would not have gotten any data. This was a high-risk mission due to the weather in the region and all the new things we were trying. We came back with all the data we set out to get and, quite frankly, I am surprised. We had a large team that helped with this project including the field team, logistics support, airport support, the NASA and NSF support teams and all of you for your well wishes and interest in our research. Thanks to all! Until next time, stay cool 🙂