Wallops Island, Virginia 6:00 p.m. EDT

From Jon Ranson:

I’m back at Wallop’s this evening after a quick trip back home. Last evening we made the decision to not fly today, so the DBSAR RAID could be fixed. I’m not an engineer, and couldn’t offer much to the RAID-fixing effort, so I had a little free time on my hands.

The news from here is great. It looks like the instrument is fixed and should be ready to roll in the morning. We’re planning to leave early in the morning, do a quick check-out, give a few high-fives for a healthy instrument, and then head to Maine. We should get two full days of data collection before we have to turn home on Friday evening. It’s less time than we’d planned, but it will be good time, and I’ll happily take it.

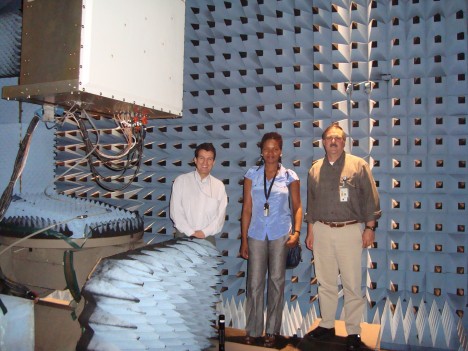

Yesterday I was under the impression that the parts had to be special ordered and would arrive early in this morning. It turns out that our engineers were more resourceful than that. They took an evening ride out to Salisbury, went shopping at Best Buy, and bought what they needed to get the job done. They got up very early yesterday morning and worked all day long on this. When I arrived around five o’clock this evening, they were still hard at work. So now, thanks to the long hours, resourcefulness and great skill, Rafael and Martin got it fixed. The DBSAR RAID looks very stable, and we expect it to work very reliably in the air.

The SIMPL team took the opportunity to tweak their instrument, too. Phil Dabney discovered that the SIMPL system was using almost all the capability of their UPS (uninterruptible power source). The instrument performed fine with the UPS, but there was very little reserve to deal with extra power needs. So the team managed to find a replacement with greater capability, and they are happier with their stability now.

Tomorrow’s plan is to get up very early, eat a breakfast and grab a “picnic” lunch at the local deli, and meet at the hangar at 6 AM. The flight crew will give us a fly/no fly decision, based on the weather situation at that time. Because that pesky hurricane is still creeping closer, there’s a bit of doubt that we’ll go, but I tell you right now, we’re all totally dedicated to getting this mission accomplished if there is a safe way to do so.

Once we lift off, around 8 a.m., we’ll fly to the Maine sites, and work hard acquiring data from all three instruments for at least 6 hours, maybe more. We’ll stay overnight near the Bangor airport, then get up early and fly another full day.

Our original flight plan called for at least four days of flight. We wanted to collect data at Howland Forest and other sites in Maine, Bartlett Forest in New Hampshire, a boulder field in Pennsylvania, and some sites in Quebec. These sites were carefully chosen to give us access to a wide range of forest types as well as a site with no forest at all (the boulder field). It’s really important to see how these instruments perform with various vegetation sites.

We also selected sites that have had recent measurements made in the field, so we can compare to recent ground truth. Many of the sites have been measured this year for the Carbon Monitoring System’s Biomass Pilot program, so we’ll be able to compare our biomass measurements against their measurements. The Carbon Monitoring System is a NASA initiative in which researchers in biomass and flux (atmospheric carbon) will create data products of carbon in terrestrial vegetation and in the atmosphere, and these products will be of known accuracy as well as be useful to end-users, such as researchers, forest managers, and policy makers.

When measuring forests, we have long considered that on-the-ground, first hand measurements are the gold standard for accuracy. When we work to improve remote-sensing instruments, it’s important to compare to this gold standard, and that’s what we are trying to do by collecting data over sites with recent ground-truth measurements collected. Using the CMS sites has the additional benefit of providing data to that program which we hope can enhance their data regarding the biomass of the area. We hope that the Eco-3D can prove very valuable to programs. like NASA’s CMS, which are designed to enhance our understanding of forest biomass well as provide data of known accuracies that can prove useful to fill a variety of needs.

One of the primary places we are interested in measuring tomorrow is Howland Forest. Portions of this forest were measured in 2009, 2010, and the CMS pilot measured some parts of it earlier this year. We have sent a crew to measure this week as well, in conjunction with our flights, so we can have ground truth that is nearly simultaneous with our instrument collections. That crew is led by Guoqing Sun, a scientist from Goddard. The crew members are living in cabins near the forest, and have been out every day gathering ground-truth data for us.

Another scientist, Miguel Roman, is driving a car through the areas we plan to measure with Eco-3D. He is surveying the sites visually to gather impressions we can compare with the flight data, and is also taking measurements of aerosol thickness with handheld sun photometers. This helps the program in various ways – since our instruments are gathering information through the atmosphere, it is helpful to quantify that variable.

The entire campaign is designed to have a week-long set of flights to the north, a week-long set of flights to the south and some local flights in Maryland over sites where the forests have been extensively measured by NASA very recently, both for the Carbon Monitoring System and other NASA research programs. In conjunction with that, we have field crews out taking various measurements. The goal is to gather as much data as possible, in as many ways as possible from specific sites. The sites are chosen to give us as many types of forest as possible – from the boreal forests in Maine to the Mangrove forests in Florida.

Despite being forced to compress a week’s measurements into two long days, we’ll still have plenty of time and flight hours to gather excellent data and produce a good result. Weather permitting, we’ll be in the air and gathering that data early tomorrow morning.

Wallops Island, Virginia 5:30 p.m.

From Jon Ranson:

This morning started out just perfect for collecting data from the air. It was a beautiful sunny day with good weather, and we did our best to take advantage of it. We were up in the air early and take-off went well, without a hitch. The check-out flight for DBSAR wasn’t quite so good.

We’d hoped that the instrument check out portion of the flight would prove our DBSAR to be sound, but that didn’t happen – the intermittent problem showed back up. We had to land at Wallops again, and hoped we could fix it quickly. But no quick fix was available. Our engineers will need to order a part and then do a major fix of the DBSAR. Or more specifically, the RAID for the DBSAR.

RAID stands for “Redundant Array of Independent Disks”. It is basically connects five discs together, and distributes the collected data across those discs, so we can collect high volumes of data very quickly. The RAID has experience two problems. First, the discs don’t sync up correctly with the computer. The second is that is they sometimes don’t record at a fast rate. Sometimes they only record at 30% of expected speed, so this really limits the data that they can acquire. So we can’t use the instrument like it is, we really have to fix it before we make our science flights.

Last night we planned on making to Maine today and making measurements, but the nagging problem with the RAID meant we had to do a thorough check out and see if we could get it fixed. We did the checkout, and it is clear there’s no immediate fix available.

After studying weather and timelines, we’ve decided that we have one day to fix the RAID. If it can be fixed tomorrow, we’ll fly Thursday and Friday. If the instrument is still being stubborn on Thursday morning, we’ll likely have to scrub the entire set of flights this week, and I’m not sure what that will mean. We need to find a way to collect our data, somehow.

The good news is that while we were checking out the radar we also flew 3 lines over measured forest plots at Wallops. The SIMPL instrument appeared to be working fine, and the CAR instrument also acquired good data. So all we have to do is get the DBSAR fixed, and we’re golden.

We also had a little excitement of a different type this afternoon. Well, it was very little excitement here, really, although our friends and loved ones at home sure had stories to tell. We were sitting in our meeting when a 5.9 earthquake struck our region! Personally, I didn’t feel a thing, but someone else did mentioned feel something odd. Pretty soon, though, we had people checking in to see if we were okay, so we found out about the earthquake pretty quickly. I guess there is something about the soil at Wallops, or between Wallops and the epicenter in Virginia, that prevented most of the tremors from shaking us up.

And if earthquakes and stubborn instruments aren’t enough, there’s this giant hurricane threatening the east coast. It’s in the Bahamas now, and our weather is beautiful, but it is tracking towards us and predictions are unclear how soon it may arrive. If it speeds up, it may impact our return flight home. None of us want to be cut off from home as Irene works her magic here, then comes calling in Maine. So any decision we make will take the storm forecasts into close account.

You know, this is a pretty good illustration of what science in the field can be like. Sometimes it sounds fairly glamorous to be a scientist and travel around and do cool things – at least that’s what I’ve been told. And yes, field work can be fun, no doubt about it. But a field campaign really is work and like any other work, it can be both difficult and frustrating. The malfunctioning instrument is just part of the picture. Such stuff happens, and we’ll get it fixed and move on. The earthquake and hurricane? Well, they are just a little bonus excitement. I’m betting we’ll get at least some good data before this section of the campaign ends, despite all the challenge.

So our plan is to give Rafael Rincon, the DBSAR Principal Investigator and Martin Perrine, the DBSAR Instrument Engineer, a full day to fix the RAID. If they can get it fixed and tested on the ground by the end of the day tomorrow, then we’ll fly early Thursday morning. We’ll then fly up to Maine, and do an extended day of measurements over Maine and New Hampshire, but we’ll have to delete the site we’d hope to fly in Canada. We’ll also fly Friday, and hope to return to Wallops Friday night. If necessary, we can come home on Saturday. At this point, our next move depends on the RAID. Oh, and I guess Hurricane Irene gets a vote, too.

I do want to say that everyone here is working really hard. Everyone is cooperating and in a good mood despite the troubles. The flight crew, too, is very helpful to our team and they, along with everyone, are working hard to make this mission succeed. Flights are risky business, and they don’t always go as planned. In the end, we’re going to get our data, I am just sure of it. Meanwhile, we’ll work hard and enjoy our work as much as we can.

Wallops Island, Virginia 9 p.m. EDT

From Jon Ranson:

It’s a beautiful evening here at Wallops Island! I’m here to join our Eco-3D team, and I’m sure looking forward to starting our flight campaign tomorrow morning. I’m really excited to be a part of the mission, and expect to have a good week gathering great data.

My name is Jon Ranson, and I’m one of the science investigators with the DBSAR. In this blog, I’ll be the one speaking to you, but I’m not actually doing the writing. I’ve discovered that on field campaigns that the science team- and usually me especially – stay too busy to spend time in the evening sitting down and writing. We can write – and we do – but while we’re in the field, we have other work to do. What I’ve found works best for everyone is to let a writer carry our story for us. For this effort, our writer is Joanne Howl. She will be staying at the home office in Maryland, taking our phone calls, and telling our story in a blog that will appear hear as near-real-time as conditions allow.

The Eco-3D mission focuses on measuring the three dimensional structure of vegetation. To accomplish this, we are combining three innovative instruments to take simultaneous measurements from a single platform – something that has never before been done.

We plan to collect aerial data from over many very diverse sites – several in the northern U.S., several in the south, and several in Maryland. We also are going to be using ground truth measurements collected on the ground at those same sites to help validate our instruments.

We currently have a crew in Maine taking forest measurements there in advance of our flight, and hopefully will be measuring as we fly overhead, too. We’ll also collect data from other recently measured sites, such as measurements make a few months ago by scientists working with the Carbon Monitoring System biomass pilot program. Their measurements support their efforts to quantify carbon in forests as well as defining the accuracy of their estimate, and we consider their field work very valuable and helpful for our own efforts. We also hope to provide them valuable data for their own research.

So why do we want to measure three-dimensional structure of vegetation? Well, let me first say that by measuring vegetation – and forests in particular – we can estimate aboveground biomass. If we know the biomass of a forest, then we can estimate the carbon stored in that forest. The more accurate the measurements, the more certain the carbon estimates.

Traditional remote sensing instruments have relied on two dimensions – length and width – just about forever. This type of measurement gives us a lot of information about forest structure and biomass, but it’s still missing quite a bit –it’s missing the entire third dimension. It’s missing height.

So why is height important? Imagine you have a photo taken at the top of a cliff, looking down. You’ve got length and width in that photo, so it’s two dimensional. Now imagine that image suddenly becomes three-dimensional. As your brain processes the added data and your mind measures the sheer drop, the image would appear more nearly real, and you might feel dizzy or frightened. That third dimension allows for a better estimate of the reality of the scene. In science, the third dimension will allow us to make a much better estimate of the height of the trees, and that is a powerful measurement to have when trying to estimate biomass.

We are carrying three instruments on the P3 aircraft, We have the Digital Beamforming Synthetic Aperture Radar (DBSAR), the Slope Imaging Multi-polarization Photon-counting Lidar (SIMPL), and the Cloud Aerosol Radiometer (CAR). DBSAR collects polarimetric and interferometric data to validate biomass estimates. SIMPL is a multi-beam, micropulse, single photon ranging laser altimeter, and will provide measurements of forest canopy structure with very high spatial resolution. It also will collect two-color polarimetry data that can be used to differentiate stand types. CAR is an airborne multi-wavelength scanning radiometer that can measure spectral directional reflectance over uniform forests, homogenous clouds, and bright targets. We’re interested in biomass, so during our campaign, CAR will be employed to derive the Bidirectional Reflectance Distribution Function (BRDF) and the vegetation clumping index.

These instruments are great, but they are new versions of older instruments, and do not have a long history of field use in this manner. They’ve only been flown together once before, and that was just this summer. The data from those flight lines look really good, but it’s not realistic to think that the installation and testing of these instruments would go entirely smoothly. And it hasn’t.

Last week our engineers began to install instruments on the NASA P3 Orion. That went well. The engineering check out flights showed the instruments and the plane can work well together, with no problems. The instrument check out, however, uncovered some hitches, some with each instrument. The engineers have fixed most of the issues, but we still seem to have an intermittent problem with the DBSAR. Most of the time it works fine, but occasionally it loses bits of data. The tough thing is that it only seems to have problems when it’s in the air, so that’s a real challenge to figure out. But we have great minds here, and I’m sure the engineers will get the job done, whatever it takes.

We’re planning an early morning take-off, and we’ll run an instrument check out first thing. If the problem appears again, we’ll return to Wallops and fix it. When the DBSAR works, we’ll head to Maine and start making our measurements. So I’m off to bed – tomorrow will start early and may well end up being a very long day.