What do you see when you go on a research cruise?

This is the most common question I get asked when I enthusiastically tell stories of our adventures at sea. For most people, the word “cruise” means travelling from one place to another (often islands or coastal cities) by sea. Our research cruise apparently has only one destination: the ocean (when we are lucky we are trying to get close to a float, that is moving in the ocean). No islands, no fishermen villages, no coastal party towns: just water everywhere. Isn’t it a boring view?

Different people may have different views on the subject, but my answer is without question a solid “no!”. And it’s not just because of the incredible wildlife that we get to encounter sometimes in the open ocean (we have been lucky to come across pilot whales and a range of seabirds), the beautiful dark skies at night and the sunsets, but mostly because of the ocean itself. Every day the ocean is different: the waves are different, the rhythm at which it shakes you out of bed or gently rocks you into sleep is different, the white caps patterns in the water are different and the color can be very different because of the color of the sky and the amount of sediments or phytoplankton in the water. When we left San Juan, Puerto Rico, the water was an energetic, smooth, solid blue, while in the northern stations that we reached the color was ranging between a silver-looking gray (on cloudy days) and a greenish aqua color. Right now – 3 a.m., it’s plain black. Ok, maybe that’s cheating.

Views from our flight from Dallas, TX to San Juan, Puerto Rico. On the left, differences in ocean color near some Caribbean’s’ islands. On the right, a sediment-rich river plume (possibly from the Mississippi River) encounters the Gulf of Mexico blue waters.

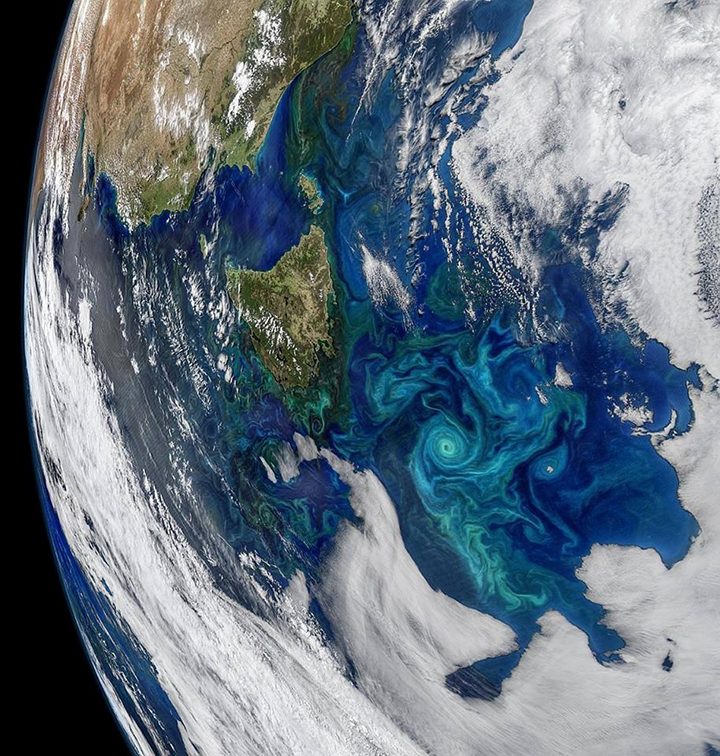

These differences in color are not just a treat for salty fishermen, oceanographers and sailors, but can be detected from planes and even satellites equipped with special sensors (and some very good images can be found here: https://oceancolor.gsfc.nasa.gov/)! When clouds do not cover the surface of the ocean, it is possible to use the color of the ocean to study the distribution of sediments and chlorophyll abundance in the ocean (and this can be used to estimate how much phytoplankton is there). Indeed, many satellite oceanographers spend years studying maps of “how green and how blue is the ocean” and how such maps change between years, seasons and different regions. Maps of this kind also helped us planning our samples, to make sure that we observe the different oceanographic conditions that characterize the North Atlantic: areas that can be as different as a forest from a desert can be just a few currents (and hundreds of km) away and if we want to understand anything about the ocean, we need all the help that we can get!

A satellite image of surface chlorophyll off the coast of Tasmania, Australia, highlights how different can be the color of the ocean even within a few hundreds of kilometers of distance. (NASA)

Written by Alice Dellapenna