I try not to make this blog a travel diary, but sometimes an event is worth a sidebar. So, before I launch into words about our voyage planning, I must tell you about the flying fish.

No matter how many times you go to sea, flying fish are a wonder of nature. Just the fact that we see individual fish scooting above the surface for long distances (many 10s of yards) is amazing enough. However, there are times when the deep blue surface of the water transforms to a shimmering silver and miraculously turns into hundreds of small flying fish launching themselves as one in the same direction. It’s amazing to watch and hard to capture on film from a moving ship. The fish don’t fly as much as glide with “skitter,” as they touch the water intermittently and then buzz their tail at the surface like an outboard motor. With this added energy they keep themselves gliding above the water surface using their outsized pectoral fins as glider wings. They must have a tough life—with large fast fish like tuna and mahimahi stalking them from below and birds stalking them from above. However, they must have a keen sense for when to be in the water and when to launch into the air—and evolution has provided them with the means to act on the threats. How they coordinate their mass takeoffs and landings as a school is, I would guess, a mystery. It is certainly awesome!

Kyla Drushka, chief scientist.

So, I digress! Our Chief Scientist, Kyla Drushka, from the Applied Physics Lab at University of Washington has been coordinating planning and logistics for this voyage for about a year—since the end of the SPURS-2 deployment voyage in 2016. She has a complex assignment because there are 24 distinct scientific instruments or suites of instruments aboard the vessel—each with a different responsible scientist either ashore or aboard. Coordination of the sampling from all these instruments and how it interacts with the location and speed of the ship is the primary job of the chief scientist. It is akin to conducting a symphony orchestra of oceanographic measurements—all of which require special interaction with the symphony hall in order to operate properly—to make good scientific “music.” Some sensors require us to be moving fast, some slow, some upwind, some downwind, some stopped. Some require our full attention and some operate autonomously. On site, here in the tropical ocean, we are recovering instruments deployed from the ship last year, deploying and recovering a variety of devices that sample only the weeks we are here, and deploying permanently some instruments that become part of the sustained Global Ocean Observing System. From the ship itself we are making a wide variety of detailed measurements of the ocean as we move about. Kyla has listened to everyone’s requirements and delivered a symphonic arrangement that sounds wonderful in our mental rehearsal of the scientific findings. All we have to do now is execute the arrangement in the real world.

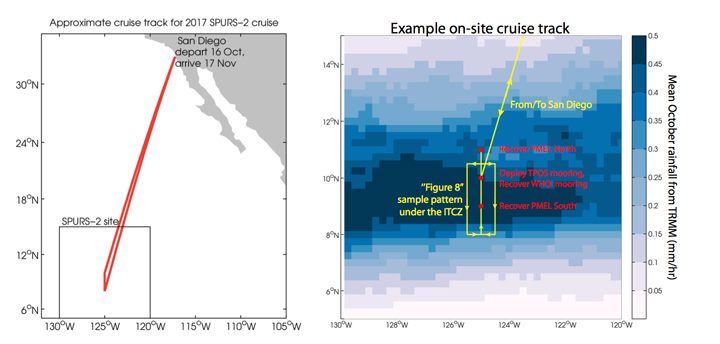

SPURS-2 cruise plan.

Overall this SPURS voyage, like others before, seeks a balance in the overall plan of action. Ultimately the goal is to learn how to interpret satellite measurements of surface salinity. This cannot be done without assessing the ocean physics that effect surface salinity and the “forcing” of signals by evaporation and precipitation. Thus, the expedition includes the ways and means for us to assess upper ocean mixing, the role of eddies in stirring the upper ocean, a detailed look at all scales of precipitation, and estimates of evaporation. Of course we cannot measure everything everywhere, so the primary role of the experiments and expeditions are to collect observations that can help us perfect computational models of surface salinity behavior that accurately mimic our satellite observations. Models can deliver estimates of what is happening around the globe and over long stretches of time – scales out of reach from ship observations. Good models lead to better prediction and we certainly need better predictions of ocean behavior for high quality predictions of climate. That kind of impact is what motivates the SPURS team.

The video below shows the view from a small boat as scientists approached a mooring in order to change some batteries. The R/V Revelle is visible in the background. (GoPro video by Raymond Graham/WHOI Mooring Group.)

Finally, as I was drafting the paragraphs above, a sea bird landed on the stern of Revelle. Not just any sea bird but a Peruvian booby. This bird is either blown of course and needs a rest or I need to go back to Booby identification school! I bid you farewell for the day and hope offended birders will tell me how unusual it is to find a Peruvian Booby at 125W, nearly 20 degrees north of the equator.

An off-course Peruvian Booby?

One of the issues that is never far from one’s thoughts on a ship is preparation for emergencies. We are a long way from first responders or help of any kind. Therefore, crew and passengers (us scientists) need to be prepared to help ourselves and our mates. This blog is meant to reassure those ashore that your friends and family on Revelle are safety conscious and prepared for emergencies.

Revelle is a very safe and capable platform. It is outfitted with an enormous array of equipment whose sole purpose is to save lives and alert the world if we have any emergency aboard. On Revelle we have weekly drills to rehearse actions in case of the three most likely emergencies. Those three things are fire, man-over-board, and abandonment of the ship. If we were in some other place in the world a fourth emergency would also be on our rehearsal agenda – piracy! Piracy is not a concern out here in the open Pacific Ocean, but in some areas of the world it would an urgent issue for crew and passenger training.

Life rings at the ready on the aft deck.

During drills we learn where to go for various alarms, what to bring, and what we (passenger scientists) might be expected to do for that particular emergency. In case of fire, the crew is highly trained and the science party would likely be moved out-of-the-way to a safe spot. However, we do need to know how to raise the fire alarm and the different kinds of fire extinguishers available. Obviously initial action can be critical to stopping a small situation from becoming a major crisis. In case of man-over-board, someone must alert the bridge immediately, keep eyes on the person in the water, and begin getting floating objects into the water (kind of trail of breadcrumbs that can lead the ship back to the person). In case we are called to abandon ship, everyone needs to know how to launch a life raft (we have plenty!) and be familiar with the communications equipment available in the rafts.

It is not hard to find a life raft should we need one.

Another issue entirely, and more of a daily concern, is working safely on deck at sea. Oceanography often involves movement of heavy equipment on a platform that may be rocking and rolling and slippery with rain or sea water. Common sense safety requires everyone to be outfitted with a floatation vest and a hard hat during deck operations. It is also common sense to take precautions at night NOT to work alone.

A bin of hard hats ready for a hardworking scientist.

Finally, there is the issue of how our personal safety impacts all aboard. We are in a confined space so illness can spread fast. That means that we must all pay attention to the public health, such as hand washing and reporting health issues. One must pay careful attention to the hazards one may create in our work spaces. The illness or injury of one person potentially impacts everyone’s projects and the overall expedition. So, overall, there is a increased awareness and devotion to safety when at sea.

I don’t think anyone on the home front should worry about us. All of us are looking out for one another and the crew of Revelle has an awesome commitment to safety and functioning of the ship.

The sunset as seen from the ship on October 18, 2017.

Going to sea slows one down from the hectic sprint of modern city life and car travel. We travel slowly (~12 mph) over the vast Pacific Ocean. It is a five-day journey to get to our “office” in the Inter-Tropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ). The “work day” will change from 8 hours per day to 24 hours per day. There are no weekdays and weekends, only workdays and off-hours. As your blogger, I look into all the projects aboard ship and fill my day with writing, photographing action, and fact-finding for my reporting. I aim to provide a new blog four days-per-week (Tuesday-Friday). If needed I serve on a shift where extra hands are required.

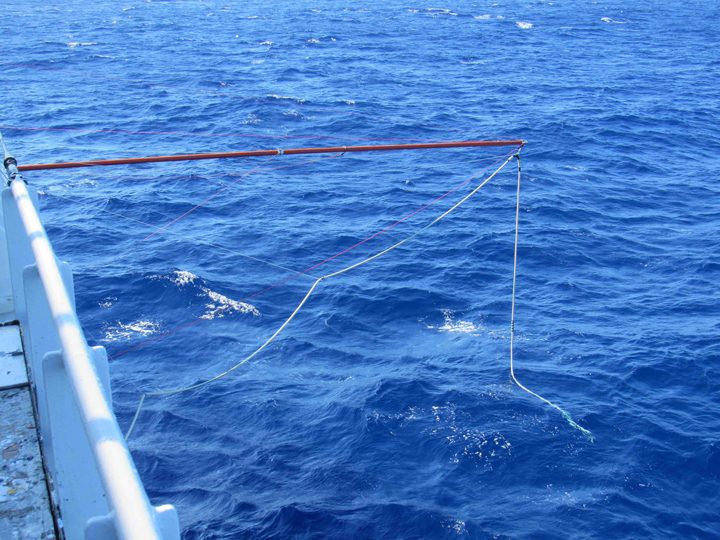

A highlight of our departure from San Diego was being greeted by a large pod of small toothed-whales (porpoise/dolphin family). They seemed as curious of the ship as we were curious of them. We had slowed the ship as we passed the Coronado Island group (off northern Baja, Mexico) to deploy a 42-foot boom off the starboard bow. This is the support structure for Julian Schanze’s “salinity snake” that provides a “clean” intake of surface water outside the wake of the ship. I imagine the whales had never seen such an operation before!

The 42-foot boom for the salinity snake.

The first two days at sea have been calm and sunny. This has been great for the newbies to get their sea legs. As far as I know no one has suffered severe sea sickness.

In the midst of our five-day commute we stop or slow down for training on occasion. Everyone needs to learn or refresh their knowledge on how instruments are deployed from the ship and safely recovered. This is the time to make sure all gear and personnel are ready for action. I will tell you more about the instruments and projects over the next month. Shipboard life is best when everyone is busy and every project is assisted to full success. During these initial days at sea there is much “cross-training,” you come to sea for one project, but you immediately train to assist on other projects.

Training class at the underway CTD winch.

As we move slowly south to the tropics we also have some small assignments to accomplish on behalf of the oceanographic community. We will deploy some Argo floats along the 125W meridian. These temperature and salinity profiling devices join a global array of nearly 4000 floats that monitor the upper 2000m of the ocean.

We know our 24/7 work begins when we reach 11N, 125W and begin the process of recovering the NOAA mooring that has been there for the last 13 months. There are three moorings in the SPURS-2 array and all will be recovered on this voyage. Generally, these moorings become teeming islands of life in the open ocean environment, attracting their own ecosystem of fish. So, fishing gear will also be at the ready and we can expect tuna and mahi-mahi for dinner the day of a mooring recovery.

Finally, it looks like there will be some Halloween celebration aboard R/V Revelle. The Captain has brought pumpkins for a carving contest. I hear that some people have costumes at the ready. I am sure some unique nautical and oceanographic twists can be brought to Halloween. We shall see. Never underestimate the imagination of people confined to a ship for five weeks!

Pumpkins at the ready for the Halloween pumpkin carving contest.

Yesterday, Monday October 16th, I joined the Research Vessel (R/V) Roger Revelle for five weeks at sea in the Pacific Ocean. It feels great to be heading to sea again. This NASA field campaign has lasted more than a year, with intense shipboard work starting in August 2016 and finishing with this voyage in October-November 2017. A web of sensors has been deployed to monitor one oceanic region over an entire year. The primary goal of this voyage is to provide one last intense snapshot of the ocean and to recover moorings and other gear deployed over the last year.

The R/V Roger Revelle in San Diego just before departure.

Scientists take one last look at San Diego as we depart.

The history of SPURS, from SPURS-1 in 2012-13 in the North Atlantic Ocean to SPURS-2 in the eastern tropical Pacific Ocean is captured in prior blogs to this site.

As Physical Oceanography Program Scientist at NASA Headquarters for the last 20 years, my primary job is supporting our satellite missions related to measuring physical characteristics of the ocean (principally, temperature, salinity, sea level, and winds) and supporting the oceanographers that generate knowledge from such data. True understanding requires our fully appreciating the variations of the satellite data in the context of ocean physics. That requires getting out there and getting wet from time to time.

R/V Revelle (home port – Scripps Institution of Oceanography, San Diego, CA) departed San Diego on 16 October 2017 and returns to San Diego on 17 November. The central location of the field work is about 5 days voyage southwest of San Diego at 10N, 125W. Details of the expedition plans are available here. I hope to bring you a steady stream of expedition blogs between now and mid-November 2017, including why NASA is focusing attention on this particular spot in the open ocean.

Since NASA’s launch in June 2011 of the Aquarius instrument to measure ocean surface salinity from space, the agency has embarked on field campaigns to understand surface salinity in great detail. This work has illuminated new ways of thinking about the ocean’s role in the global water cycle. SPURS-2 is the latest work to link the remote sensing of salinity with all the oceanic and atmospheric processes that control its variation.

The ocean is the primary source of moisture for the atmosphere. Evaporation of water from the sea surface leaves the ocean saltier (more saline). Precipitation over the ocean leaves the ocean fresher (less saline). The global pattern of average salinity at the sea surface approximately represents the balance of evaporation and precipitation at any locale (other factors such as river runoff, ice melt, and ocean motion and mixing complicate the picture). Many details of the interaction between ocean and atmosphere that lead to moisture transfer and signatures in ocean salinity are poorly understood. SPURS-2 is particularly focused on how, in one of the rainiest places on Earth, rainwater enters and impacts the ocean. During the blog in the coming month, you will hear more about how and why oceanographers focus on such a problem.

In 2012-2013 SPURS-1 in the North Atlantic Ocean focused study of ocean processes where evaporation dominates the salinity of the surface ocean. I blogged during the September 2012 work from R/V Knorr. Among other things, we learned that surface salinity variations in that part of the world can be directly connected with precipitation patterns over the nearby continents.

At the opposite extreme from SPURS-1, SPURS-2 focuses on an oceanic regime where precipitation dominates the salinity characteristics of the surface ocean. The two extremes call for significantly different approaches to measuring and studying the upper ocean. We use many of the same tools from SPURS-1 (instrumented moorings, profiling floats, surface drifters, and gliders) but deployed in new and novel ways.

The crew and scientific party on R/V Revelle almost 50 in all. As you read future blog entries you will get some sense of what its like for such a group to work closely together for five weeks in the confined space of an oceanographic research vessel. Seasickness? Food? Watches? Sleep? Drama? Boredom? Sea life?

So, if I get this right, and you continue to follow this blog, you will get a sense of how some oceanographers go about their work, what technologies are involved, what is discovered, and how all this impacts lives, including yours, and what you might experience if you were aboard. I’ll do my best to get this right!

Eric Lindstrom, physical oceanography program scientist at NASA Headquarters, and blogger for the SPURS-2 campaign.