We have been traversing the South Pacific for over thirty days now. Early on, we had several days of high winds and rough seas with waves that may have been as big as 8 meters (over 25 feet). The bow of this gigantic vessel would sometimes submerge under a giant wave that sent thumps and reverberations throughout the hull of the ship. During those days, giant albatross followed the ship and showed off their flying skills. They would glide with great speed over the peaks of these waves and down into the troughs. At the bottom, they would make a sharp turn and catch the air current generated by the water motion and appeared as if they were surfing along the face of the wave.

We’ve crossed several time zones and, for the first time in my life, I have experienced ‘boat lag’ and had to adjust my sleeping to compensate for the changes. It is difficult to distinguish one day from the other. Each morning I rise, have my coffee, and read the news via AP wire. After grabbing some breakfast, I prepare all of the filtration equipment in the lab. Next, I clean, adjust, and focus the FlowCam, an instrument used to image microscopic organisms in the water. Usually by the time that is completed we are on station (our daily stop to lower the instruments down deep into the ocean). We get suited up into our protective gear then go out on the back deck to deploy our instruments and pump sea water into large Nalgene containers with a spigot to dispense the water. We bring the water samples into the lab and spend hours filtering the water through different types of filters.

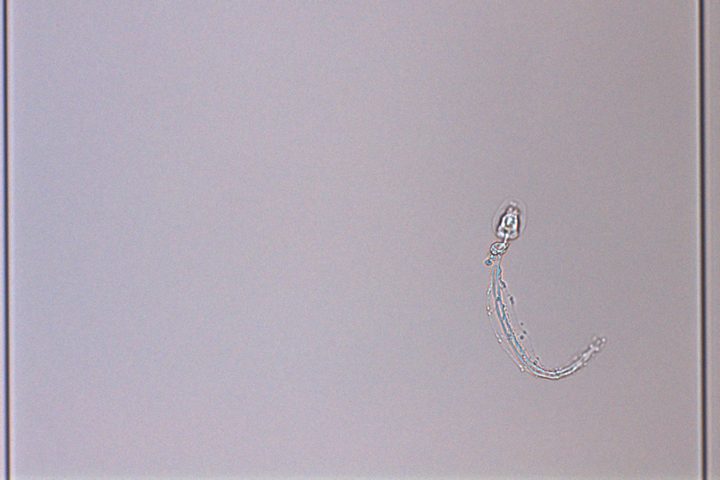

A transparent marine worm, called Chaetognatha, seen through our flow through imaging system (FlowCam). Credit: Mike Novak/NASA

Back in the labs at NASA Goddard, we will analyze the particles that got trapped on the filters as well as what went through, or the dissolved portion. It’s all valuable information about the microscopic life in this part of the ocean and helps us understand the role each plays in Earth’s carbon cycle.

The days here are long and repetitive. Sometimes I’m on my feet almost nonstop for 10-12 hours. When seas are rough, the boat is constantly moving and I have to compensate all the time for that movement while I stand, move, or walk. There are crew members, engineers, marine technicians, and scientists from many disciplines and institutions on this expedition. Everyone works hard and does their best to keep morale and spirits up. People organize cribbage and ping pong tournaments. Sometimes it is hard to find the time where shifts and availability match up to compete, but it is a good way to have some fun if you can find some down time.

When the seas are calm and daily duties are done, people play ping-pong inside the ship. Credit: Mike Novak/NASA

On clear nights, I go out on deck where the stars can be so magnificent and I gaze deep into the universe. The Milky Way stretches across the sky from horizon to horizon. Since we are in the southern hemisphere, we see many constellations and celestial objects that people in the northern hemisphere cannot see. The Southern Cross is a very prominent constellation while the two Magellanic Clouds are neighboring galaxies that are an impressive sight, even with the naked eye. In the south, the image of the moon is inverted compared to viewing it from the north. The new crescent moon waxes, or increases size, from the left to right instead of the reverse direction that I’m used to seeing back home.

An unobstructed view of sunsets and sunrises over the ocean are an inspiration to see. Many of us try to meet out on the helipad after dinner to watch the sun dip below the horizon. When the clouds are positioned just right, it appears as if they become electrified and the sky lights up with brilliant reds and pinks. The reflection of the majestic show on the surrounding sea gives the whole effect a greater sense of awe.

Two sunset photos with slightly different states of calm and cloudiness. Credit: Mike Novak/NASA

The ship ran out of vegetables and fruit several days ago and having a fresh garden salad is something I dream about. I miss my wife and my family. I miss our garden and our house. I miss feeling the damp earth under my feet and feeling the green grass between my toes. I miss the sounds of birds, insects, and animals scurrying through the forest. I miss going to concerts, museums, and making music with friends.

There are many musicians on board, including myself. I try to sneak away for ten minutes here and there to strum my classical guitar and work on new and old songs. We get together and play sometimes as well. It is difficult to find a place that is quiet enough where we don’t disturb other people. However, we were lucky enough to have a jam session out on the bow on one afternoon when the wind and waves were fairly calm. Being surrounded by the sea with the sun on my face is a great inspiration for music!

The boat has giant diesel engines and there is no way to escape their thunderous roar. The repetitive nature of this work is challenging. Every day I follow a similar schedule of working, eating, exercising, and sleeping. There are no days off and there is always more work to be done.

Despite all the hardships of rocking on the seas for 40 days, I feel that our work has great meaning. For several decades, the science data collected on these repeat hydrographic research cruises has been analyzed and published in peer reviewed papers. The breadth of knowledge that comes out of this program and the previous ones that it is built upon contributes to understanding the bigger picture of how the ocean ecosystems are responding to the changing ocean and atmosphere. The work that we do here, and what other have done in the past, will help us to understand and mitigate the problems of future.