Waking to a dry morning, I sluggishly dawdled to the water dispenser where my housemate was staring at a strong column of ants.

“They’re back in force. We should do something about them.”

It was a predictable biological event pattern – one that happens whenever there is a long spell of dry heat.

I thought about it for a moment, “We could get some powdered diatomaceous earth and spread that around.”

“What is that?”

“Fossilized shells of diatoms, so it’s mostly silica. I think it absorbs lipids from an ant’s exoskeleton, causing it to dehydrate and die.”

“That’s kind of brutal – aren’t diatoms the phytoplankton you’re growing?”

In fact, they were. Inside our laboratory at UC Santa Barbara, I had been cultivating marine diatoms, photosynthetic microscopic plankton found throughout the temperate oceans. Some estimates project that they produce up to 20% of the oxygen we breathe. They also often contribute to one of the most striking and predictable biological events in the oceans, the annual North Atlantic spring bloom – an event so striking that it can be seen from satellite images!

As primary producers, marine diatoms transform carbon dioxide and inorganic nutrients into the organic matter they need to build their cellular mass and fuel their activity. Through a few processes, that organic matter is released into the water as a dissolved source of food and carbon, DOM (dissolved organic matter), to marine bacteria.

Professor Craig Carlson and I study DOM because it supports the activity of marine bacteria, prevalent and important members of the oceanic food web, and because it represents a fraction of carbon that can sway the balance of carbon dioxide between the ocean and atmosphere.

A chain of marine diatoms imaged by the onboard Imaging Flow Cytobot (IFCB).

In the months prior to this NAAMES mission, we were working hard to tag DOM produced by our diatoms with a non-radioactive isotope. Our intent was to concentrate the tagged DOM and feed it to natural populations of marine bacteria that we collect and incubate in bottles. If successful, our use of the material would allow us to observe and compare the specific types, or taxa, of marine bacteria that use DOM produced by blooming phytoplankton.

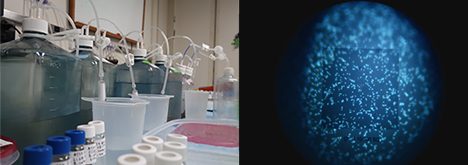

Left: Sampling some of our growth experiments to quantify DOM, cell numbers, cell carbon content, DNA, and enzyme activity. Right: Microscopic view of marine bacteria from our growth experiments, fluorescing with a nuclear counterstain.

The North Atlantic is notorious for being unforgiving and furious, often making it difficult for scientists to gather samples and perform experiments. Though it has upheld its reputation by slamming our vessel with up to 50-foot waves, it also graced us with its gentle nature, providing us with a unique opportunity to witness and study the spring phytoplankton bloom. Thanks to both calm conditions and the more than capable help from all the Atlantis crewmembers, Craig and I were able to not only collect more than all of the samples we needed, but were also able to spin up every bacterial growth experiment we hoped to conduct – including our DOM feeding experiment.

Although it will take many months of processing and analyzing our samples before we can procure firm results and conclusions, we expect to generate a dataset that will be informative to our understanding of ocean chemistry and ecology.

We’ll be back to do it all again – but first, I’d like to test how diatomaceous earth might inhibit the predictable summer ant invasion into our house.

Representatives from UCSB’s ocean optics and microbial oceanography groups. Front, left to right: Stuart Halewood, Associate Development Engineer, and Craig Carlson. Back, left to right: James Allen and Nick Huynh, Graduate Student Researchers. Photo: Pete Gaube

Written by Nick Huynh

Dear sir/mam.

i’m interested going to NASA so what’s the procedure for going..so please let me know