After escaping from heavy seas, we are heading back to port. This will be not a short travel, it will take about 5 days to arrive at Woods Hole. But all the time and effort of science team and crew members are worthy in order to explore one of the most amazing ecosystems: oceans.

One drop of seawater is a whole microbial universe. I like to imagine this micro universe as a jungle, full of organisms of different kinds and sizes, predators eating others for meals, bunches of little organisms working together to produce food or defeat a stronger one which eventually will be a meal, or even some guys eating the leftovers of a big feast. In these descriptions you can imagine jaguars, ants, piranhas, or vultures, but no, I am talking of tiny living beings such as bacteria, copepods and protists.

There are many ways to classify these microbes: by size, shape, or which functions they carry out in the community, just as we do with animals and plants. Sounds easy, but is not; these features are difficult to describe in microorganisms simply because, well, they are micro. Even with the best microscopes available, microbial characterization is not an easy task, and that is where our job starts. As all living beings, microbes contain a genome made of DNA inside their cells. The genome is a whole set of instructions which allow the correct development and functionality of the cells. We take advantage of a set of genes (pieces of the genome which codify for individual instructions) that are common for all organisms and can be considered a fingerprint. The more similar this print (sequences of DNA components) is, the more probable we are talking about the same kind of organisms. So, we use this genome segments to classify the community of the samples collected at different stations and depths across the North Atlantic Ocean.

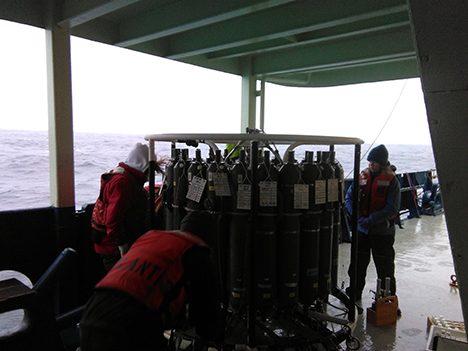

The CTD rosette where sample water is collected from different depths within the ocean. Photo: Luis Avellaneda

Doing this classification we can calculate at each sampling point the relative abundances of the different species that comprise the community, our microbial jungle. Why is this important? Well, imagine some part of this magnificent micro-jungle where we cannot see any bananas left in the banana trees; that would be a very strange situation, but if we know that in that jungle area the abundance of monkeys is very high, we can figure it out what is happening there. The same thing occurs in the microbial universe, certain organisms prefer to consume or produce specific compounds.

Having a high-resolution characterization of microbial species composition and how this composition changes at different sites or times, help us to correlate them to the different data that my ship fellows are generating. In that way we can describe this invisible jungle, their dynamics, and the collective consequences that these lively drops of water are producing in our planet.

North Atlantic common dolphin. Photo: Luis Avellaneda

Written by Luis Avellaneda

Really enjoyed your narrative!!