The CPC is counting 100 particles/cm3, which is 10 times lower than you normally breathe in room air. We breathe the fresh Atlantic marine air and marine aerosols. The size of particle is less than 500 nm, which is invisible, you can’t even feel it and you can’t take a photo with your iphone. This beautiful day begins with the Ion Efficiency calibration for our instrument high-resolution time-of-flight aerosol mass spectrometer (HR-ToF-AMS) on our transition day. My colleague, Maryam, helped replaced the dryer with her stronger muscles. The selected 300 nm ammonium nitrate particles were generated by atomizer and Differential Mobility Analyzer (DMA) and to calibrate AMS ion efficiency. The flight time of 300 nm ammonium nitrate particles in the ToF vacuum chamber is 0.003 second, which you can image how fast the small particles fly through the 0.295 m pToF chamber. Controlling particle number concentrations with a needle valve is not difficult today makes this calibration went smoothly. A lot of IE calibration and daily data analysis today keeps me busy. Of course, having a cup of coffee and green tea is my everyday drinks.

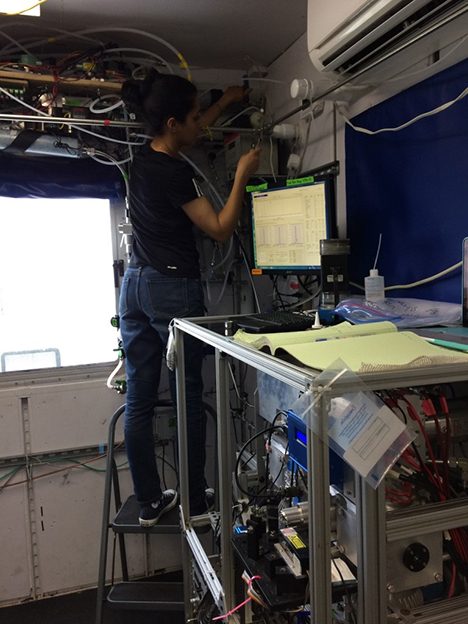

Maryam is replacing dryer in Russell group’s van. Photo: Chia-Li (Candice) Chen

Bow view when walking outside of aerosol vans.

Every hour in our shift time we check every instrument by VNC remotely monitoring SP2, AMS, Met station, filter switch program, SEMS, OPS, and APS. The largest issue of our AMS instrument is the heater oscillation problem. The AMS heater temperature is set to be 600 degree C when the AMS acquiring ambient data. However, the heater remains fluctuation, manually adjusting it is the easy way for now. Taking apart electronic parts is always the last solution against this issue. The AMS electronic board has mysterious route that connects heater power, transistor, and thermocouple to the tiny vaporizer in the AMS chamber, which only the smart UC Irvine engineer, Cyril, can conquer the difficulty. Fortunately, the AMS has been working well except for the AMS DAQ software bugs problem, AMS monitor replacement yesterday, and one turbo pump died because of over temperature.

The computer lab becomes silent at 2:30 PM since most of scientists are resting for the coming station, only the hiss sound following the movement of ship can be clearly heard.

Single-particle measurement by event trigger mode of AMS is my major work on this ship. What’s event trigger? An event can be a single particle or can be a gas signal event. Even though the Atlantic marine aerosol concentration is low as ~ 1 μg/m3, as long as there are particles existing in the air, which can be measured and triggered by the optimized event trigger levels that was set for which mass-to-charge regions of interest we are looking at. The amazing of this newly developed method is that we can understand more about the external mixing property of single particle. It’s not only single particle with organic chemical composition or sulfate particle suspended in the atmosphere. It could be mixture particle that affects climate change, visibility and phytoplankton in the ocean. The mysterious cycle and relationship of air, ocean, phytoplankton, DMS, VOCs, fine particles, CCN are linked together without breaking any linkages. That’s why we are here.

The food on the ship is so delicious that I can easily gain weight. My favorite food is always seafood… today is blackened Mahi.

My lunch and dinner.

Written by Chia-Li (Candice) Chen

When people hear I am heading to sea for a month I am regularly asked: “What is the food like?” Often this is accompanied by a pained expression, as if the questioner is concerned I will waste away being fed like Harry Potter when he is home for the summer holidays. There is no cause for concern – the food is always good. On the Woods Hole ships the food quality has moved beyond good and is now “so good it’s bad”. I am a serial offender when it comes to overeating. A good example was today at lunch. I queued up (this totally satisfies my British nature!) and observed the options:

Black and red bean with roast carrots and beets soup

Turkey meatball and cheese sub

Smoked salmon and avocado sandwich

Roast cauliflower/broccoli and cheese quiche

Manicotti

Hummus and pitas

Meatball sub and Manicotti from today’s lunch menu.

In my head I tried to limit my intake. “OK, I’ll just have the salmon sandwich and some quiche.” This was before I arrived and actually saw the wonders on offer. Suddenly my brain wants me to try everything and I’m confused by what to choose. About 50 hungry scientists and crew are patiently waiting for me to make a decision. Panic sets in and I end up with a plateful of everything I intended plus the Manicotti. It tastes gooood though. Failure has never been so wonderful.

With limited self-control over my eating, exercise is the only weapon with which to fight back against weight gain. Some people walk all around the ship, up and down the many stairs. Some use exercise videos and weights. Crewmen Ronnie and Neumann do Muay Thai, an impressive if somewhat terrifying kickboxing spectacle. I just try to use the running machine. Running while the ship moves around is best described as like running on a very poorly-maintained and undulating track…….but with your eyes closed. You get minimal warning that the lovely descent you began a few seconds ago is about to turn into a challenging ascent. The treadmill is not your friend – it is oblivious to the ship’s rolls and keeps you running at the same speed irrespective of the pain inflicted. This machine has an ‘incline’ setting, I assume purely to help define the term ‘irony’.

The dreaded treadmill in the science hold.

As you may have gathered, by this point in the cruise we have settled into our routines in sleep, food, exercise and science. Everyone has already collected a good amount of data and/or samples. Our group is looking at DMS, a sulfur gas produced by the biological community in the ocean that plays an important role in atmospheric particle formation. Our group’s custom-built mass spectrometers have been working well, analyzing water and air samples. They’ve been running with minimal issues (unlike last time out!), which has allowed us to look at the data and tweak the setup to ensure optimum results. There’s nothing worse than getting home and realizing that we should have done things differently! The weather forecasts for the next few days suggest we will catch a big storm so we are excited to observe a large transfer of DMS into the atmosphere – fingers crossed!

Bow mast which is used to mount the 3-D sonic anemometer, accelerometer, and gas inlet leading to the mass spectrometer. Photo: Thomas Bell

Written by Thomas Bell

By Walt Meier

I have arrived in Barrow, Alaska. It was an interesting flight up from Anchorage: the plane had seats only in the back half of the plane because the front half is used for cargo. That is because there are no roads into Barrow, so supplies need to be brought in by plane or, during the short summers, by barge. After a stopover in Prudhoe Bay, we arrived to gloomy skies, which are quite typical for this time of year. Temperatures are right around freezing. We are staying at the NARL, which originally was the Naval Arctic Research Laboratory. Various research groups and other activities –even a college– now share this facility.

The accommodations are spare, but comfortable. Most people are staying in Quonset huts (prefabricated huts made of galvanized steel), but I’m with four others in “The House”, which is more like, well, a house. We have a living room, kitchen, full bath, and four bedrooms. Because we have a kitchen, we are the base for meals where the whole group meets up to eat breakfast and lunch. Last night we all gathered for a light meal after arriving and, with 24 people, it got pretty crowded. But it was nice to catch up with old friends and meet new colleagues. Already the collaborations have begun as we informally discussed each other’s research.

The whole campus is on a narrow spit of land north of town sticking out into the Beaufort Sea. I can see the sea ice from the house. So you might say we’re staying at a beachfront resort! With the ice right out the window, it was tempting to take a walk out there last night. However, we were told to not go out on the ice until we get a safety orientation. The ice off the coast is landfast ice – ice that is attached to the coast, so it doesn’t drift with the winds. However, it can still shift with the tides, as evidenced by piles of ice ridged formed as ice got pushed together. So one doesn’t want to just run out on the ice without being familiar with the hazards. Oh, and there are also potentially polar bears roaming around – another very good reason not to go roaming off by oneself.

Our view of sea ice from The House.

Now we’re heading off to our orientation session and introductory discussions where we’ll start learning about modeling, satellite data, and field observations. This afternoon we’ll take our first trip out onto the ice. When the week is over, each of us will have broadened our expertise beyond each of our core research areas and hopefully we may find new areas of research to collaborate on and advance our understanding of sea ice.

By Walt Meier

Whenever I tell people that I’m a polar scientist or that I study sea ice, inevitably one of the first questions I’m asked is, “so, have you been to the ice?” I’ve always had to answer no. I’m a remote sensing scientist who works with satellite data. Other than a few aircraft flights over the ice several years ago, I’ve spent my career in front of a computer analyzing satellite images. When I’ve needed field data, e.g., to validate satellite measurements, I could always obtain it from colleagues. So there has never been any need for me to go out on the ice. And to be honest, spending days or weeks in the field, as many researchers do, does not have particular appeal to me – I like the comforts of my heated office! Nonetheless, I’ve always wanted to get out at least once in my career and see the ice close up, feel it crunching under my feet, hear it creak and groan as it strains under the winds and currents.

An image of sea ice in northwest Greenland, captured by NASA’s Operation IceBridge.

Now I am getting that chance, thanks to a National Science Foundation funded Summer Sea Ice Camp workshop. I and a couple dozen fellow scientists are heading to Barrow, Alaska – the northernmost point in the United States at 71 degrees N latitude – to partake in a unique project. The goal of this project isn’t specifically to collect data (though I hope that some of the data we collect will be useful), but rather to foster communication between remote sensing scientists like myself, sea ice modelers, and field researchers.

While there is a lot of collaboration in the sea ice community in terms of sharing data and results, scientists tend be silo-ed within their own area of expertise when it comes their actual work. Modelers focus on model development, validation, and results. Remote sensing folks like myself analyze satellite data. And field researchers collect and analyze in situ observations. Partly this is simply due to time – just focusing on one area keeps one plenty busy. But it is also partly due to a lack of communication. For example, I know a bit about modeling, but I don’t really understand the details of how a sea ice model is put together, how it can and should be used. Similarly, while modelers often use remote sensing data to compare with their model results, they don’t often understand the capabilities and limitations of satellite data. This can lead to under use or misuse of the data. And neither modelers nor remote sensing scientists may have much understanding of how to best take advantage of in situ data.

The goal of this workshop is to bring the three groups together for a week to talk and work with each other to better understand each of the three specialty areas and how perhaps the three groups can better work with each other to advance our understanding of sea ice. So now I’m on my way to Barrow, Alaska, looking forward to helping others understand satellite data, as well as running sea ice models and feeling that crunch of ice and snow under my feet as I collect data from on top of the Arctic Ocean. More in my next blog post from Barrow!

The Dark Side of Optics at Sea & The Development of Boat Brain

The old adage of Murphy ’s Law states that: ‘If there is the opportunity for something to go wrong then it will inevitably happen’

Well for all Oceanographic engineers it’s obvious that Murphy spent a considerable amount of time trying to get instruments to work at sea. It seems that sometime during the transition from dryland happy bench testing, to onboard rocking and rolling ocean ops there is an attitude shift in either or both the equipment or the operator.

Inherent Optical Properties-IOP frame and suspicious operators. Photo: Stuart Halewood

Whether it is swapping connections on obviously labelled instrument plugs, to forgetting to actually switch units ‘on’ before sending them into the abyss. To the random erratic behavior of previously rock solid sensors. Murphy pops up in the strangest of places to answer the frustrated cries of ‘but why?’ from the research engineer or scientist.

For the equipment this could be forgiven as now it’s in a new and pretty hostile environment, varying temperatures, high pressure of the ocean depths and someone throws it off the back of a rapidly moving platform without so much as please or thank you.

For the operator the same issues apply except, hopefully not the ocean depth and being thrown into the sea bit! That and the development of what we jokingly call ‘Boat Brain’. The seeming loss of your ability to do the things you’ve done a thousand times before just because you are now surrounded by moving salty water.

The challenge for us is to listen to the instruments, check everything, check it again and then get someone else to check! Take your time and be safe. Rules to follow in every aspect of being at sea.

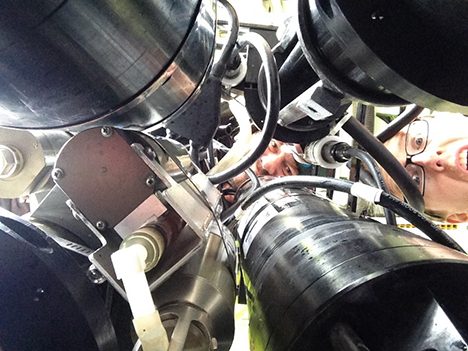

James Allen checking the Optical Tubes on the IOP frame. Photo: Stuart Halewood

While there is a dark side to us taking measurements at sea with somewhat delicate instruments on a research vessel, there is also literally a dark side to our optical measurements. Contrary to logical sense, we actually deploy one of our optical instrument packages at 10:30 at night! The IOP Package is a specially designed instrument package that uses its own light, in the form of bright LEDs or lasers, to make measurements and record both optical and physical oceanographic data.

We lovingly call it the optical disco ball, because we see many colors of the flashing lights before it gets sent to the depths of oblivion. With the information from this cast, we can check how optical constituents change from daytime to nighttime, when critters migrate great vertical distances to feed.

Night Time deployment of the IOP frame. Photo: Nicholas Huynh

As for what these creatures think of our brightly colored USO (Unidentified Sinking Object) in their midst, we are uncertain but we hope they appreciate the light show.

Written by Stuart Halewood