I’ve asked Stuart to write a short description of the scientific background behind the dive program that is at the heart of the research cruise that I have been fortunate enough to participate in and that description can be found at the bottom of this journal entry. However, I wanted to try and graphically illustrate what these amazing folks have done three times a day, every day of this cruise regardless of conditions.

People may think that diving on the equator must be a pleasure and that all you have to do is strap on a tank, put on some flippers and a mask and jump over the side. In reality, because of the cold upwelled waters of the equatorial undercurrent, particularly in the western part of the Archipelago, it is really hard and bone chilling work. I’ve watched as the two teams of divers somehow manage to stuff themselves into two layers of neoprene with boots and hoods and gloves — certainly not what one would expect to wear for diving on the equator. However, even with all this, the divers emerge after nearly an hour and a half under water with their lips a nice shade of blue and shivering under the hot equatorial sun. I’ve watched as they’ve draped their arms and legs around the sides of the pangas, trying to capture any bit of heat that the dark rubber hulls may have absorbed from the sun, looking remarkably like the marine iguanas, basking on the black volcanic rocks after they have spent a much shorter time underwater grazing on the beds of algae.

So here is what a typical day is like for the scientists/divers onboard the M/V Queen Mabel as I’ve watched them over the past week although, I can’t imagine that diving in such an incredible place with such amazing marine life all around you could ever be considered “typical”.

The Dive Teams

The Panga Drivers

After taking the divers to the dive site, the panga drivers try and maintain their positions above the divers, keeping an eye on their bubbles and standing by in case there are any emergencies. If all goes well, and I speak of this from personal experience after having kept them company for a number of dives, being what I like to call “shake and baked” for the nearly hour and a half that the divers are down, the divers surface, raise their arms and the panga driver races over to pick them up, help lift their tanks and gear aboard and takes them back to the Mabel as quickly as he possibly can.

Suiting Up — With a Little Help from a Friend

As mentioned above, diving in most parts of Galapagos is not what you’d expect and a great deal of time is spent by the divers in trying to fend off the effects of the numbingly-cold upwelled water of the equatorial undercurrent that bathes the western parts of the Archipelago. Trying to insert oneself into two layers of neoprene wet suits is not easy and is similar in many respects to the extrusion of sausage into its casing, only without the help of a machine. Getting that last zipper zipped more often than not requires the help of at least one and many times, two friends.

Heading Out to the Dive Sites

After having made sure that all the gear they will need has been placed onboard the pangas, the teams head off to their respective sites finding their locations through a combination of visual memory and a hand-held gps receiver. It is critical to the goals of this program that the same sites are revisited as closely as possible so that changes over time can be correctly assessed.

After they arrive at the site, final checks of gear are made, regulators tested, masks defogged, measuring tapes, writing slates and sampling bags are gathered up and on the count of three, the divers fall backwards into the water, purge the air from their buoyancy vests and sink beneath the waves.

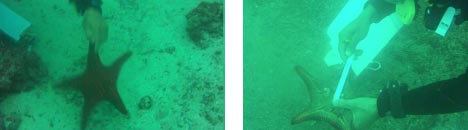

Under the Sea

Back in the Panga

Assuming that everything has gone well, the first diver surfaces approximately eighty to ninety minutes after submerging and the panga driver races over to meet the divers as they emerge and helps them back into the pangas and back to the Mabel. Conversation in the panga on the return trip is minimal compared to the trip out since everyone is cold, exhausted and just trying to focus on something other than their shivering bodies.

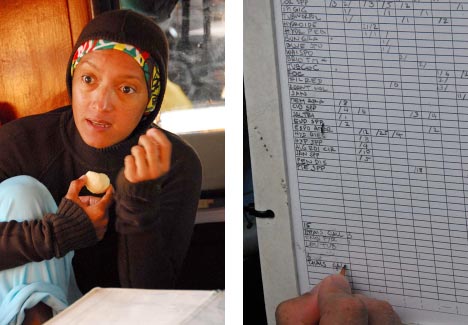

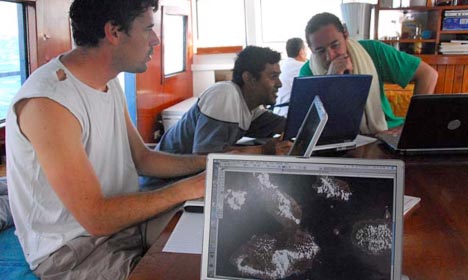

Back on the Mabel

The empty yet still very heavy air tanks are lifted from the bouncing pangas over the rail and even heavier filled ones are passed down to take their place for the next dive. Dive suits are peeled off, rinsed and hung to dry for a few hours, the divers rinse off with the cold water foot pump shower on the dive platform, data from the dive are entered into everyone’s computer, Angela sorts through the little plastic bags of invertebrate specimens and identifies them with the aide of a reference book and the combined knowledge of the divers before placing them back into the ocean. The empty air tanks and gas tanks for the pangas are refilled and before very long, it’s time to do it all over again.

Stuart Banks’ description of the Dive Program

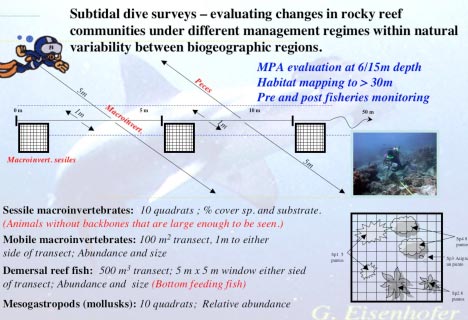

Subtidal community monitoring works to characterize the near coast underwater communities across the entire Galapagos Marine Reserve (GMR). It’s part of a long-term project to follow change in the coastal zone across the different bio-geographic regions in the GMR, from the cold upwelled communities dominated by macro-algae stands in the western islands, to the last remaining coral reefs in the far northerly islands of Wolf and Darwin. The overall goal is to gauge how the marine reserve is changing between seasons, between years, under El Nino / Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and with different types of extractive (fisheries) and non extractive (tourism) activities. Every year we follow more than 64 fixed sites which were approved between all GMR stakeholders in 2004 in order to evaluate the effectiveness of the coastal zoning — one of the principal management tools applied by the national park service in the reserve.

What that means in practice is a LOT of dive work. Two groups of 3-4 people simultaneously dive at replicate sites over 22 field days per season which works out at around 40 hours spent underwater per diver, or 240 diver-hours in total (10 days!) for the 6 person team. Each diver is specialized in 2 types of monitoring. Laying 50m parallel transects out at 15m and 6m depths that follow the bathymetry, one diver visualizes a 5m x 5m corridor alongside each side of the transect and estimates the size and abundance of all fish, noting also turtles, sea lions, penguins and cormorants — even the occasional giant manta ray or dolphin. The second diver counts and measures sizes of all mobile macro-invertebrates in a 1m band either side of the transect — sea cucumbers, sea stars, lobsters, octopus, sea urchins, nudibranchs and large marine snails. The third diver has perhaps the most challenging task — laying quadrants every 5m along the 50m transect they catalogue every sessile algae or animal under an 81 intersection grid — that’s 1620 measurements per sampled site across the two depths. They record everything that grows upon the seafloor — corals, algaes, sponges, tunicates, hydroids — usually hugely diverse and in general quite difficult to identify. Over recent years the list of new species has gone up as we have improved our base line taxonomy. Today we’re routinely covering over 1000 species of the 2800 registered to date in the marine reserve and the list keeps growing.

Since 1994, Charles Darwin Foundation divers have monitored over 2000 x 50m transects — that’s equivalent to 3-4 divers swimming over 100 km, sampling sub-tidal communities. It sounds a lot, but still compared to the 1670 km of coastline, it is still less than 5% of the total reserve. Of course on top of that there is also pelagic monitoring — diver drift dives for large fish and sharks that live in open water, regular monitoring of coral plots, habitat mapping, oceanographic work with Conductivity Temperature Density (CTD) profiles, satellite sensor ground truth measurements, plankton net trawls, recruitment traps for fish and lobster, experimental work with settlement plates, directed searches for threatened species, species level work to study foraging behaviors of higher vertebrates such as penguins, cormorants sea lions and fur seals, impact assessments for installation of low impact moorings, surveys of hull growth for invasive marine species, tagging for site fidelity of sharks, deep water exploratory work with remotely guided submarines, fisheries population monitoring with the National Park Service…. All run on a shoestring.

So as this trip draws to a close, we can say that for 2009 we again have our finger on the pulse of the marine reserve — information that will be processed and passed onto decision makers. There is a lot of work still to do — particularly with making sure that the information gathered is used in the elaboration of a new management plan for the marine reserve with the National Park.

I never would have imagined such daily hardship and toil undertaken so cheerfully by so few for the benefit of knowledge advancement of billions. Amazing.