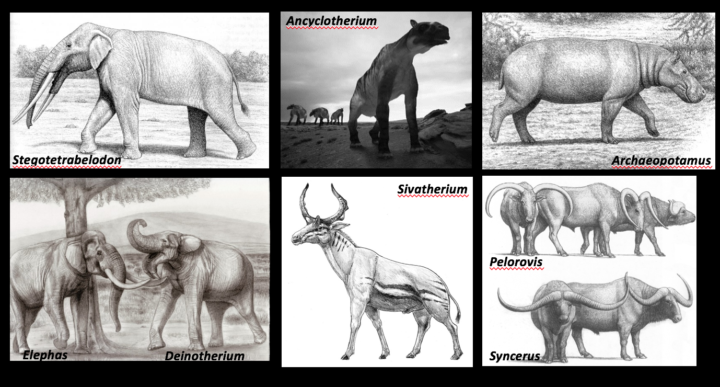

Seven million years ago, some truly spectacular creatures roamed the woodlands of East Africa. There was a moose-like giraffe called Shiva’s beast. There were giant buffalo with horns wider than the animals were tall. And the lumbering creatures known as anthracotheres defy easy categorization.

“Whenever I ask colleagues who study anthracotheres how they describe them, they always say: hippo-pig,” laughed Tyler Faith, curator of archaeology at the Natural History Museum of Utah. As for the buffalo: “This was a horn span of 3 meters (10 feet). I mean this was an awesome buffalo.”

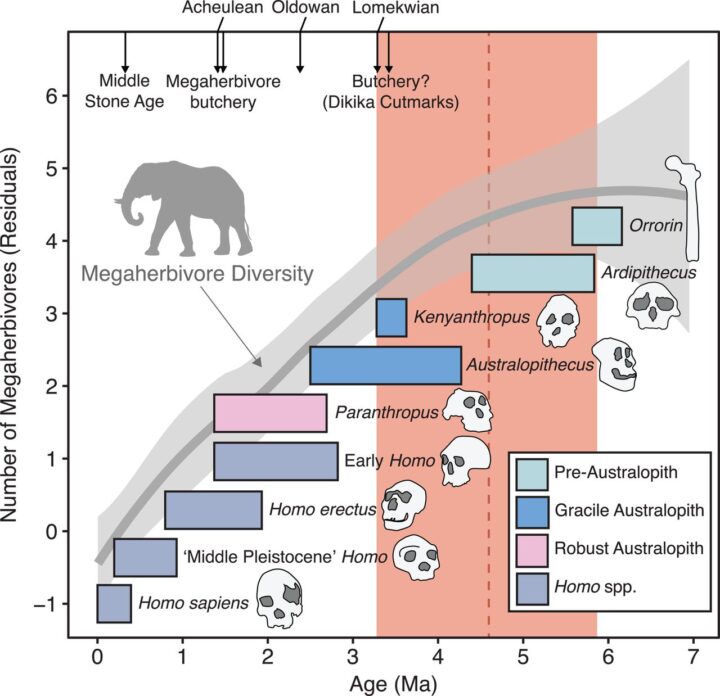

These and several dozen variations of more recognizable African megaherbivores — elephants, rhinos, hippos, and giraffes — all went extinct within the past several million years. For decades, archaeologists have pinned the blame on early humans, particularly Homo erectus, a species that emerged 2 million years ago, walked upright, and had a body plan similar to modern humans. Since Homo erectus made stone weapons and was capable of butchering large game, many archaeologists assumed that it hunted Africa’s megaherbivores into extinction — much like the fossil record suggests Homo sapiens (modern humans) did to the large mammals of North and South America some 11,000 years ago.

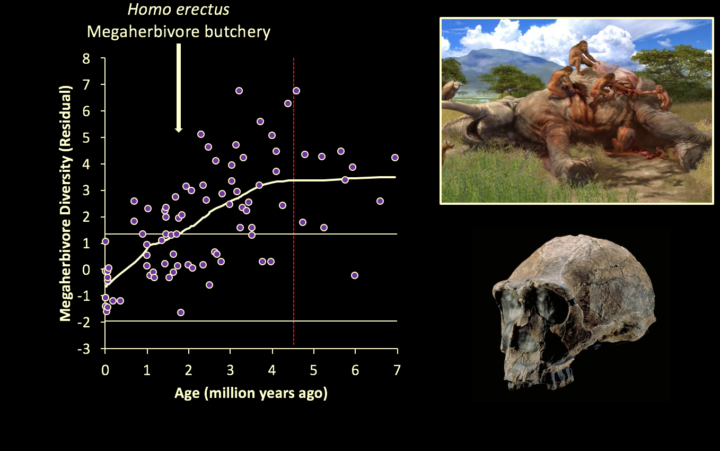

But nobody rigorously tested whether this “overkill hypothesis” fit with the fossil record. “Speculation had been repeated often enough that it just graduated into fact; it became the truth,” Tyler explained during a recent colloquium at NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center. To check more rigorously, Tyler and colleagues analyzed fossil assemblages from 101 sites in Eastern Africa.

What they found was a surprise. Megaherbivores began disappearing about 4.6 million years ago — long before Homo erectus came on the scene (1.8 million years ago). And there was no increase in the rate of extinctions even when Homo erectus and butchering showed up in fossil records.

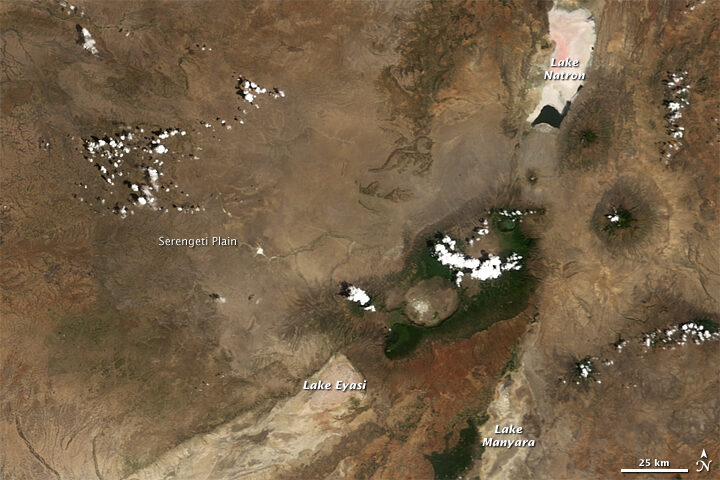

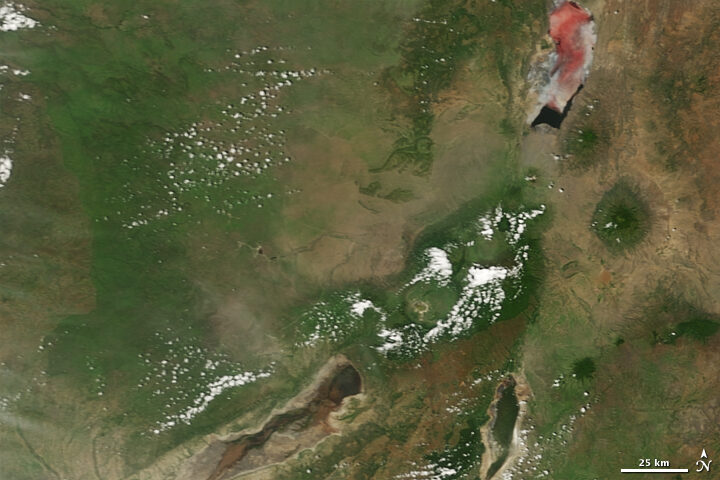

However, when the researchers looked at some key indicators of past environmental conditions, they found one key change — the expansion of grasslands — lined up with the extinctions almost perfectly. Five million years ago, classic open grasslands like today’s Serengeti Plain did not exist in East Africa. Trees and shrubs were a much more dominant part of that African landscape then, explained Tyler.

But as carbon dioxide levels declined, mainly due to orbital variations and changes in the amount of Earth covered by ice, forests retreated and grasslands became dominant. Since many of the megaherbivores fed mainly on woody vegetation, they likely faded away along with their food sources. Meanwhile, other familiar species thrived. The ancestors of wildebeest, hartebeests, Thompson gazelles, oryx, plains zebras, and warthogs — all grazers that live in open habitats — proliferated.

Faith’s bottom line is that it is time to stop blaming Homo erectus for something they didn’t do. “In the search for ancient hominid impacts on ancient African ecosystems, we must focus our attention on the one species known to be capable of causing them – us, Homo sapiens, over the past 300,000 years,” he said.