The winter of 2016–17 brought a mild and relatively brief La Niña to the Pacific Ocean, and it now appears that 2017–18 could offer a repeat. On the scale of La Niña events, the conditions developing in the eastern and central Pacific are not yet remarkable, and forecasts suggest they will remain mild. Nonetheless, some familiar atmospheric effects are rippling around the globe.

La Niña is the cooler sister to El Niño. La Niña draws cool water up from the depths of the eastern Pacific, energizes the easterly winds, and pushes warm surface water back toward Asia. (Note the ripples of warm water moving west across the equator.) In turn, global atmospheric circulation and jet streams shift with the changing heat and moisture supply from the vast Pacific Ocean.

During La Niña events, the weather tends to grow warmer and drier across the southern portion of North America, from California to Florida. Cooler than normal temperatures usually prevail across western Canada, Alaska, and the U.S. Pacific Northwest. Over the central and eastern Pacific Ocean, clouds and rainfall become more sporadic, while rainfall tends to increase dramatically in Indonesia and the western Pacific. Weather conditions in late 2017 seemed to fit with that pattern.

After a pattern-defying burst of rain and snow during the La Niña winter of 2016-17, Southern and Central California fell into one of the driest times ever in the region, according to Bill Patzert, a climatologist at NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. He noted that the region has so far received just 4 percent of normal rainfall since the water (rain) year began on October 1. “Normally, our wettest months are January, February, and March, so there is still a little hope,” Patzert said. “But the La Niña, the notorious ‘diva of drought,’ taking up residence at the equator does not bode well for winter rainfall.”

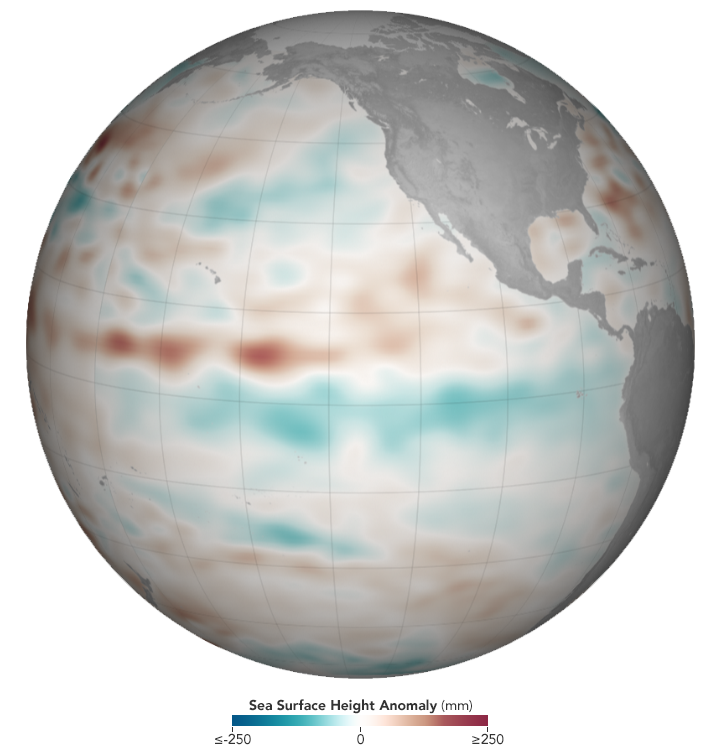

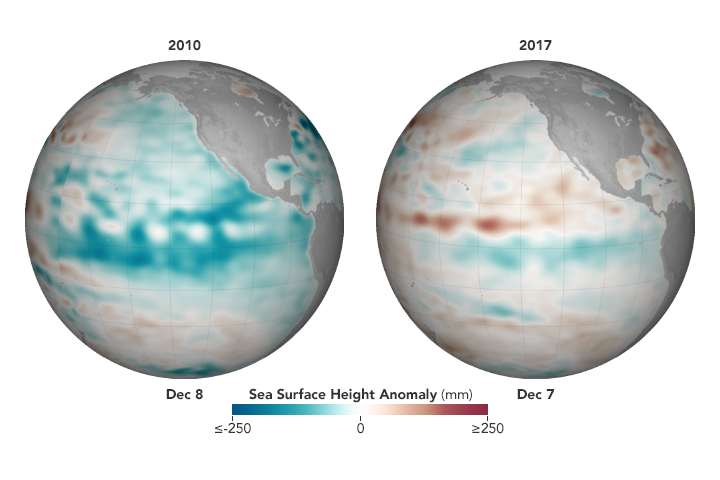

The globe at the top of this page shows Pacific sea surface height anomalies on December 7, 2017, as analyzed by NASA scientists. The animation and globes below show 2017 conditions compared to 2010, during one of the strongest and longest La Niña events on record. Eastern Pacific temperatures in 2017 crossed the La Niña threshold from September to November and may still be developing.

The measurements were made by altimeters on the Jason-2 and Jason-3 satellites, and show averaged sea surface height anomalies. Shades of red indicate areas where the ocean stood higher than the normal sea level; surface height is a good proxy for temperatures because warmer water expands to fill more volume. Shades of blue show where sea level and temperatures were lower than average (water contraction). Normal sea-level conditions appear in white.

In reports issued in December 2017 by the NOAA Climate Prediction Center and the World Meteorological Organization, climatologists forecasted that the current La Niña should last through the 2017-18 northern hemisphere winter, before changing to neutral conditions in the late spring of 2018. In early December, water temperatures in the central Pacific Ocean were roughly 1.0 degrees Celsius below the long-term average. A La Niña event is declared when average surface water temperatures stay at least 0.5° Celsius below normal in the Niño 3.4 region (from 170° to 120° West longitude) for three months. September through November 2017 marked the first such window in the current cycle.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Joshua Stevens, using Jason-2 and Jason-3 data provided by Akiko Kayashi and Bill Patzert, NASA/JPL Ocean Surface Topography Team. Story by Michael Carlowicz.