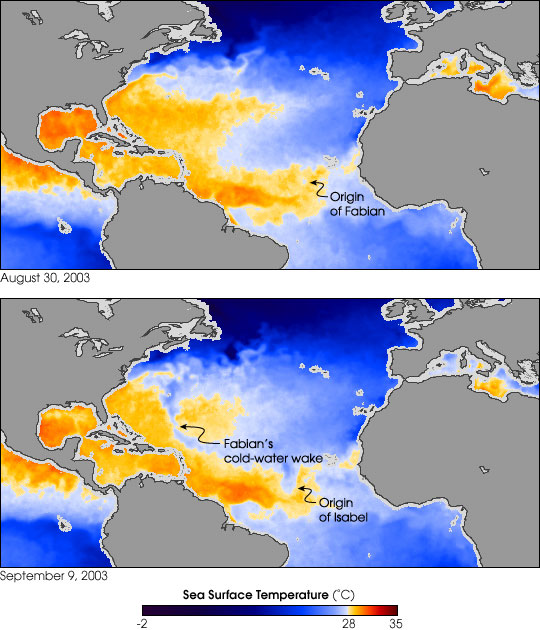

This pair of images from the AMSR-E sensor (Advanced Microwave Scanning Radiometer for the Earth Observing System) on the Aqua satellite shows the powerful effect of hurricanes on sea surface temperatures. The images show temperatures in the Atlantic Ocean after the passing of Hurricane Fabian during the first week of September 2003. Using microwave technology that can penetrate clouds, AMSR-E measured the surface temperatures in the Atlantic on August 30 (top) and September 9. Temperatures have been color-coded into waters that are generally warm enough to support formation of hurricanes (oranges and reds) and waters that are generally too cool to support hurricane formation (blues).

Surrounded by warm waters on August 30, a small dot of blue to the west of Africa shows the first stirrings of Fabian. As the storm churned across the Atlantic, it left its cold water trail as a visible track through the summer-warm waters. Interestingly, Hurricane Isabel formed very close to Fabian’s origin and, despite passing very near to the cooler waters left in Fabian’s wake, Isabel has managed to power its way up to a Category 5 Hurricane as it moves westward across the Atlantic.

The primary cause of the cool-water wake along the path of the storm is that powerful winds circling inward toward the low air pressure at the eye of the storm force surface waters outward, away from the storm. Deeper, cooler water wells up to replace the surface waters. A second reason for the cooler temperatures is that hurricanes act like “heat engines.” When most of us think of the word “engine,” we think of the engines in our cars. But in simplest terms an engine is a device or system that converts any kind of energy into energy of motion. In a car, it’s the chemical energy stored in the gasoline that engines convert into motion; in a hurricane, the storm converts the heat stored in warm, tropical ocean waters into atmospheric motion.

The swirling, spinning hurricane sprays the warm water off the wave tops, where it easily evaporates into water vapor. The heat of the ocean is latent—hidden—in the water vapor. When the water vapor rises into the atmosphere and condenses into rain, the heat that originally came from the sun’s warmth on the tropical ocean is released into the atmosphere, often far from where the storm first picked it up. This release of heat produces more wind, which kicks up more spray, which creates more water vapor, which produces more rain, which releases more heat...and the hurricane heat engine keeps churning.

Images by Robert Simmon and Jesse Allen, based on data provided by the AMSR-E Science Team and Remote Sensing Systems