large images:

October 9, 2002 (2.6 MB JPEG)

January 29, 2003 (2.8 MB JPEG)

Southeast Asia’s Mekong River flows thousands of miles from its source in the highland plateau of Tibet to its outlet into the South China Sea. The river runs through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia, and Vietnam. The giant river is a valuable, and in some countries a pivotal, natural resource, and has supported hundreds of thousands of people through farming and fishing for centuries.

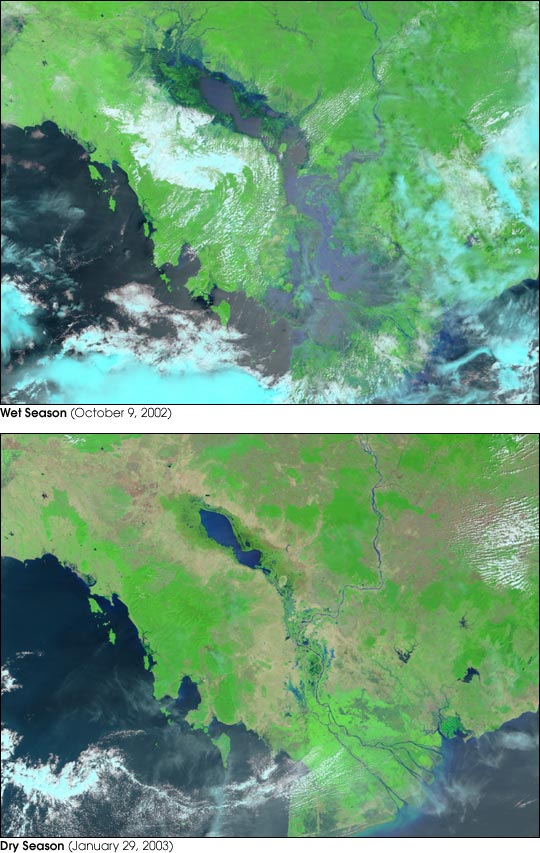

Among the most interesting features of the river is that monsoon-season rainfall swells the river’s volume so greatly that in low-lying Cambodia, one of the Mekong’s southernmost tributaries is forced to reverse course against the rushing floodwaters. Beginning in June, the roughly 100-kilometer-long (62 miles) Tonle Sap River will begin to be inundated by the rising waters of the Mekong, and will slowly backtrack and begin filling the Tonle Sap Lake. The Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) images above show the Tonle Sap during the dry and wet seasons. Vegetation appears bright green, standing water is dark blue, and clouds are light blue or white. In the bottom scene, the Mekong can be seen flowing in at the top to the right of center, and the Tonle Sap makes a distinct blue splash to the west. By October, much of central Cambodia is underwater (top scene).

The seasonal floods swell the Tonle Sap—the Great Lake—from its dry season low of a few thousand square kilometers in surface area and a depth of around two meters to as many as 12,000 square kilometers and a depth of ten meters (1 square kilometer is about .4 square miles; 1 meter is 3.3 feet). The ecological importance of the seasonal flood cycle can’t be overstated. The huge lake and surrounding wetlands created by the flooding support a diverse freshwater fish ecosystem, and the silt deposited by the floods renews forest and farmland alike. As the countries along the course of the Mekong make plans for more upstream dams and navigation channels, the seasonal cycle of the lower Mekong becomes threatened, as do the fisheries and farmlands dependent on it. What is good for one country or region might have devastating consequences for another. The governments in the area face a difficult problem as they try to balance the competing interests of flood control, hydroelectric power, shipping, fishing, agriculture, and environmental protection.

Image courtesy Jesse Allen, based on data from the MODIS Rapid Response Team at NASA GSFC