| |

July 12-14

From Taymyrskiy Region, Siberia 9:05 PM USZ6S (9:05 AM EDT)

- Weather for Khatanga, nearest city

- High: 62 degree F

- Low: 49 degrees F

- Humidity 87.4%

- Pressure: 29.83 in Hg

- Wind: 11.2 mph NE

- Visibility >6.1 miles

From Dr. Ranson

Since our last entry, we’ve broken camp twice and spent one day working in the woods on our various studies. It’s been an intensely busy time, but not without some unexpected pleasures. Our last camp was a real treat. We chose the site for its proximity to our research areas, but were pleased to find a little wooded area, up an embankment next to the river, with the ground carpeted by moss and lichens. Not many bare rocks at all! It was soft! What a great night’s rest.

Because my tent was in the woods and on high ground, I stayed snug and dry, despite being awakened in the middle of the night to the sound of a hard rain. But a few folks had set their tents in the low land, by the side of the river. The runoff from the rain went down our hill and right into one of their tents, just like little fast-flowing streams. So not everyone had a good night’s sleep at that camp.

Tonight we will again camp on a rocky beach. At least the rocks are fairly small here; we’ll sleep okay. We have the river on one side and a small stream behind us, so it’s really like camping on a big a sandbar. Even though it’s drizzling again, we don’t think the river will rise much tonight.

|

|

|

| |

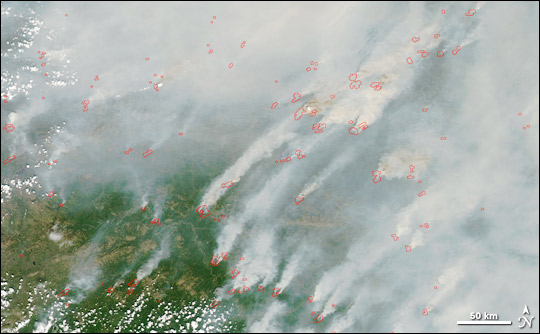

Since we arrived, we’ve had no shortage of sites we can measure. We are traveling right through areas surveyed by the GLAS instrument in 2003, 2005 and 2006. Let me explain how this all works a bit more. GLAS is a lidar instrument aboard the ICESat satellite. [A lidar is like a radar, except it uses laser light instead of radio waves.] The satellite moves along in an orbit up above the Earth and GLAS fires a laser pulse to the Earth at specific intervals. The pulses hit the Earth about every 170 meters, and some of the energy is scattered back from the surface. GLAS measures the intensity of the return signal, which is called a waveform.

Like the beam of a flashlight, the laser pulse widens into a cone shape as it travels from space to the surface of the Earth. That means the area “illuminated” by the laser pulse—the GLAS footprint—is roughly circular. When we map the results, it’s just like a dotted line across the Earth, with each dot representing a footprint and the line representing the path of the orbit.

The return waveforms are affected not only by the height of the trees, but also the branches, the understory, the ground, and anything else that exists there. We can calculate tree height from the waveform data by subtracting the first return (tops of trees) from the last return (ground). We also use these waveforms to calculate biomass.

In some areas on Earth, our calculations match closely to what we measure when we are on the ground. But, when we look at the GLAS data from this particular region, what we see is waveforms that are characteristic of bare hillsides, not forest. Yet there is forest here. I see it with my own eyes, and we’re measuring it.

We hope that our ground-truth measurements will help us interpret the GLAS data we do have. We may then be able to interpret the data we have more accurately, so we may recognize these small forests. If not, we can certainly use the data we’re gathering to put into our models, so that in the future we can build an instrument that will measure these areas more accurately.

One of the issues may be that the measurements in this region are most often taken during the winter time. These trees, although conifers, lose their needles in the winter. Without the canopy on the trees, we may be losing a lot of return data, and this may well alter our ability to interpret whether we have sparse forest or bare hillside.

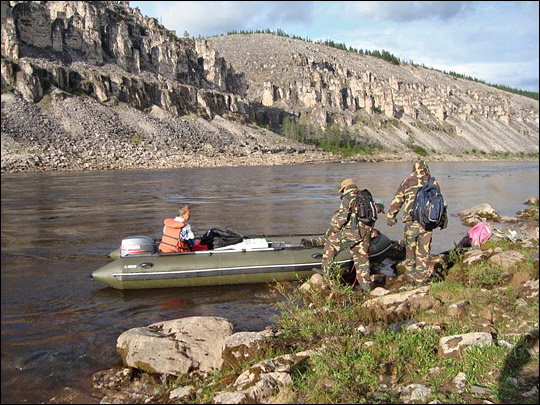

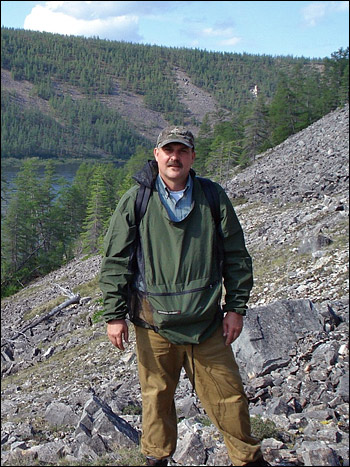

Today we’ve stopped at what appears to be the beginning of a canyon. There are a couple of pretty steep hills on each side of the river. We’re excited about this, because it gives the U.S. team an opportunity to make measurements on steeper slopes that we have seen this trip. And it gives the Russian team a great place to gather data on the effect of elevation on treelines. It’s a good spot, and we’ll work it hard tomorrow.

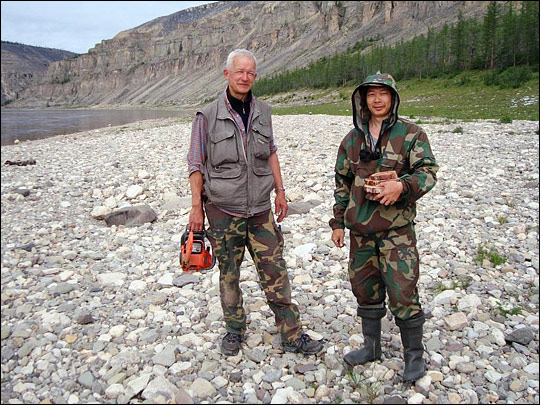

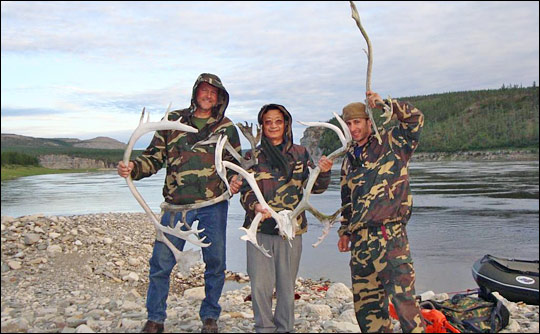

I should mention what an incredible group we have here. We all get along well and each person has so much talent. It’s always interesting when we have a chance to stop and talk together.

The newest Russian among us, Dr. Muhktar Naurzbaev, is an expert at dendrochronology. He dates the trees, of course, by looking at the tree rings: one ring equals one year’s growth. In good years, the rings are far apart, in tough years they are very close together. Because the climate is so extreme here, Muhktar must use a microscope to evaluate the width of the tree rings. Some of the rings are no more than 200 micrometers wide – just over the width of two human hairs. That represents how much the tree grew in an entire year! That’s so incredibly little! But the point is, they may have barely grown—but they did grow. The land is extreme, but life won’t quit.

These small trees here, in this tough land, can be very ancient indeed. Muhktar tells me that he has seen larch trees over 1,000 years old. The diameters are small, yes, but the trees have lived a very long time.

Yesterday we had a real treat. The sun came out for the afternoon! How wonderful to see that brilliant blue Arctic sky and feel the warmth of sunlight again! But the sunshine was short lived; it’s overcast again. At least we know the Sun is really up there trying to shine on us twenty-four hours each day. I’m sure we’ll see it again, soon.

|

|

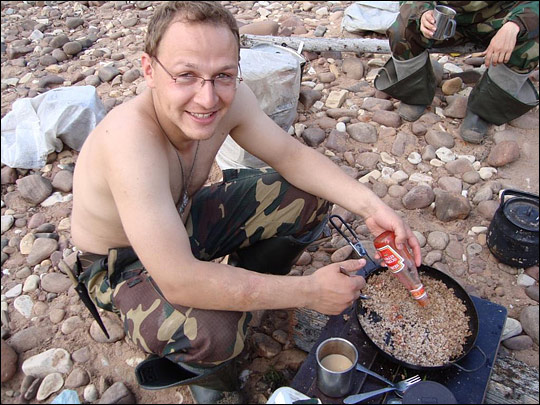

Ross Nelson (right) and Gouqing Sun (left) clean and scale the day’s catch. Fish are the only fresh protein available to the expedition, so they eat it as frequently as possible. On this day, the scientists set out nets in the morning and returned, hungry from a hard day's work, to a good catch. Twenty-five fish went into soup and, for variety, some others were seasoned and fried over the campfire. (Photograph by Jon Ranson.)

|