During the devastating 2004 Indian Ocean tsunami, more than 200,000 people lost their lives. Some coastal communities were shielded from the waves’ destruction by mangrove forests, which motivated efforts to protect and restore them.

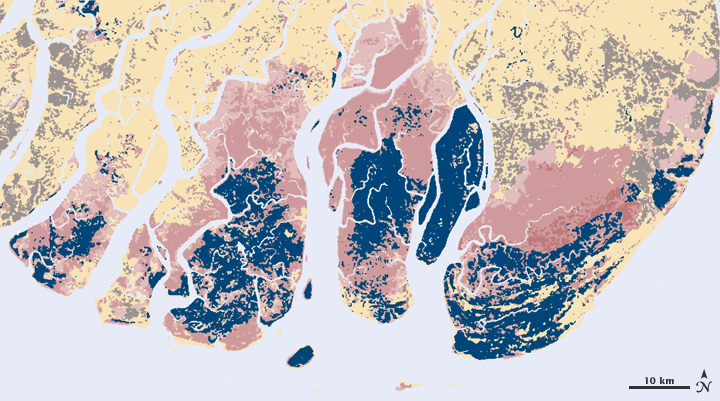

As a foundation for conservation planning, remote-sensing ecologist Chandra Giri of the U.S. Geological Survey’s Center for Earth Resources Observation and Science led a team of researchers who used Landsat images to map the extent of mangroves in tsunami-affected countries and to determine the rate and causes of deforestation from 1975 through 2000.

In some ways, explained Giri, mapping mangroves with satellite imagery is straightforward. Mangroves have a unique appearance in satellite images that makes them easy to identify. But in the tropics, finding enough cloud-free scenes is hard. Also, mangroves are often tucked into small pockets of coastline, or they narrowly line meandering creeks. When you are mapping small features, any distortion or misalignment among images can make it impossible to detect changes over time.

“The most important result obtained from South and Southeast Asia is that agriculture is the main factor responsible for mangrove destruction,” said Giri. That finding was contrary to the widespread belief that shrimp farming was the primary cause of deforestation.

When Giri and his colleagues mapped the mangroves in the tsunami-affected regions, the Global Land Survey 2005 collection wasn’t released yet. Instead, the team had to do much of the pre-analysis processing—including the orthorectification to remove distortions—themselves. It was a gigantic task that makes Giri appreciate the work that went into the Global Land Survey 2005 collection.

The surprising results in the tsunami-affected areas inspired Giri and his colleagues to expand their analysis worldwide. “For a global study of this nature, acquiring and pre-processing large volumes of Landsat data is a gigantic task for a single researcher,” says Giri. Without the Global Land Survey data, he concludes, a global map of mangroves wouldn’t be possible.