Life at the first South Pole station demanded resourcefulness and creativity, which was good for the body and the mind.

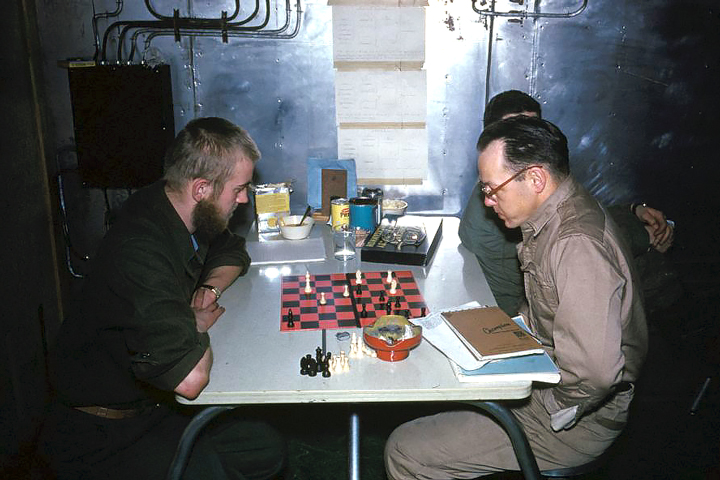

Bob Benson (left) plays chess with meteorologist Ed Flowers in the mess hall. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

One of Siple’s rules was that almost nothing should be thrown away. You never know when you might need something, he insisted, and it was thousands of miles to the nearest hardware store. Part of the base consequently looked like a junkyard.

Within weeks of settling into the base, people grew immune to each other’s germs and stopped getting sick. That left the base with a surplus of tongue depressors—enough to make ice cream on a stick. However, one night during an outdoor picnic—it was 60 degrees below—someone ate his ice cream and then discovered that he had also eaten half of the depressor. It all tasted the same at that temperature.

In the barracks, they held frequent lectures on what each researcher was working on. They also showed Hollywood movies a few times a week on a 16-millimeter projector. There was not much else to do at night. They burned their garbage every full moon, though no one knew why. It just seemed cool.

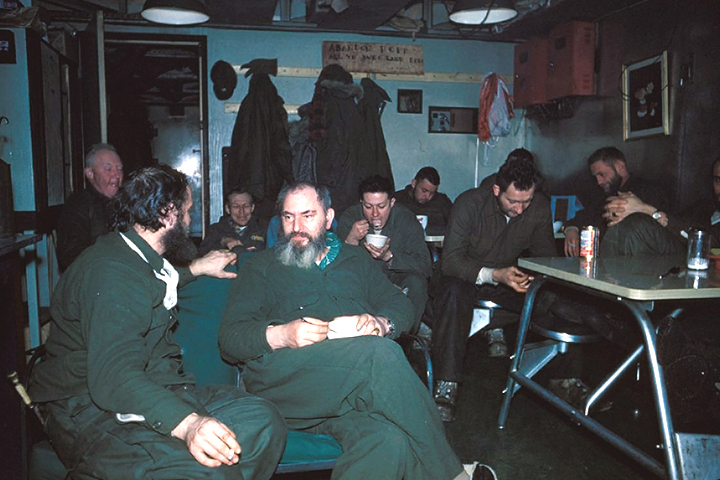

Paul Siple (center) and the rest of the team enjoy some ice cream before watching a movie—two of the few creature comforts from home. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

An outhouse was placed right at the South Pole as a joke, but it was never used. There was also an indoor outhouse in one of the buildings, but the temperature below the seat was -40 degrees. The medical doctor, Howard Taylor, devised a cover to go over the hole so at least a person could start with a toilet seat at room temperature. One man with an odd sense of humor stacked magazines next to the toilet in case anyone stayed long enough to read. No one did.

Bathing was another issue. Water wasn’t the problem: the men had miles of it frozen beneath them. Everyone was required to work several hours per week in the “snow mine.” That snow was carried in a burlap bag into the living quarters and melted with heat that bled off the generators. Showers were quick.

During his great adventure, Benson took hundreds of photographs, some of them with a rudimentary pinhole camera that he had made at the station. Once a National Geographic photographer, Tom Abercrombie, visited and encouraged Benson to submit one of his pinhole-camera photos to the magazine. It was a four-day time exposure of the Moon circling the station, and it was good enough to make a two-page spread.

Bob Benson used a pinhole camera to take this long-exposure photograph of the Moon’s path across the sky over several winter nights. (Courtesy of Bob Benson.)

After 10 months in Antarctica, Benson returned to the University of Minnesota to obtain a master’s degree in physics. He then went back to cold extremes, earning his doctorate in geophysics from the University of Alaska-Fairbanks. After one year of teaching in the astronomy department at the University of Minnesota, he then spent five decades at NASA Goddard studying the ionosphere.

Like everyone else who has ever been to the South Pole, Benson considers the trip one of the high points of his life. But he has never returned. Even crazy men eventually become wiser with age.

Though he loved his adventure, Bob Benson, now age 80, has never been back to Antarctica. (Deborah McCallum, NASA.)