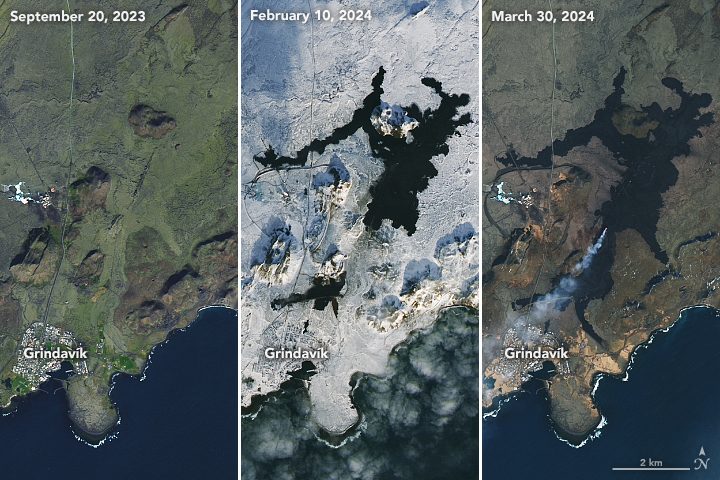

Lava poured from a volcanic fissure near the town of Grindavík, Iceland, in spring 2024. The eruption, which began on March 16 and remained active over two weeks later, was the largest in a string of four volcanic events on the Reykjanes peninsula starting in December 2023.

The OLI (Operational Land Imager) on Landsat 8 captured this image of the ongoing eruption on March 30, 2024. The natural color scene is overlaid with an infrared signal to help distinguish the lava’s heat signature. The active part of the fissure and the origin of a volcanic plume are apparent. While the eruption was still active at this time, additional satellite and ground observations indicated it was likely waning.

The eruption began at 8:23 p.m. local time on March 16, the Icelandic Met Office (IMO) reported. A fissure nearly 3 kilometers (2 miles) long quickly opened in a similar location to the February 2024 eruption. Hundreds of people at the Blue Lagoon, as well as a small number in Grindavík, were evacuated within about 30 minutes of the eruption starting.

In the days that followed, lava flowed toward infrastructure such as water pipes and roads, the town of Grindavík, and the ocean. Human-constructed barriers of earth and rock diverted lava away from town, although a flow extended across one road. Officials were initially concerned that lava would reach the coast and cool rapidly upon contacting water. This could have posed additional hazards such as the production of hydrogen chloride gas, but the flow stopped short.

This Landsat image comparison shows the recent changes on the Reykjanes peninsula. In September 2023 (left), the area was quiet volcanically. By February 10, 2024 (center), three separate fissure eruptions had occurred. The footprint of new basaltic rock grew in March 2024 (right) as new lava spanned nearly 6 square kilometers (2.3 square miles), according to the IMO.

Like the eruptions that preceded it, the spring 2024 event was effusive, not explosive. Effusive eruptions tend to emit minimal ash, and their plumes typically contain water vapor, sulfur dioxide, carbon dioxide, and small amounts of other volcanic gases.

This eruption did not disrupt air travel, but sulfur dioxide (SO2) emissions were hazardous locally at times. Workers evacuated the power plant north of Grindavík on March 18 due to gas pollution, the Icelandic National Broadcasting Service reported. The SO2 emissions from this eruption were forecast to drift across the United Kingdom and northern Europe, according to models based on satellite observations, but at an altitude too high to affect surface air quality.

Unlike the other recent eruptions in this region, the springtime event stretched out over weeks rather than a couple of days. The reason for the relatively prolonged eruption may be that magma now has an easier path to the surface, experts suggested in news reports. Others think that magma is no longer accumulating in the shallow magma chamber beneath the area and that this eruption could be the last in the longer cycle.

NASA Earth Observatory images by Lauren Dauphin, using Landsat data from the U.S. Geological Survey. Story by Lindsey Doermann.