NASA GPM Radio Frequency Engineer David Lassiter monitors the progress of an all-day launch simulation for the Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory at the Spacecraft Test and Assembly Building 2 (STA2), Saturday, Feb. 22, 2014, Tanegashima Space Center (TNSC), Tanegashima Island, Japan. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

When a satellite gets to space, the first thing it needs to do is check in with those who sent it there. NASA’s David Lassiter is the guy on the other end of the line. “My job is just to make sure E.T. can call,” he said. Responsible for radio frequency communications– RF comms–he’ll be on console the night Global Precipitation Measurement mission’s Core Observatory heads for space.

David is just one part of a large international cast, ready to push open the curtains on something that’s been in production a long time. The running crew has cleared the wings. House managers have checked the doors. On headsets all stations check in, voices clear, sharp, and spare. It’s dress rehearsal, and the combined cast and crew from NASA, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, and Mitsubishi lean into their parts as if it were opening night.

Soon. Very soon.

Years of planning, of logistics, of language training and technical coaching and set design, have led this elite corps to the performance precipice. The saying goes that a bad dress rehearsal promises a good opening night, but in this case, nobody in the bifurcated casts spread between Tanegashima, Japan and Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland will accept anything less than perfection in the run-thru.

The big show’s opening night is also it’s closing night. This will be a command performance, a one-time-only show of epic proportions attended by senior staff from two proud space-faring agencies. But like all command performances, leaders may have privileged seats but it’s the vast throng of commoners who’s interest make events memorable. Those groundlings are all of us. For a mission focused on global rainfall, the GPM launch is a show for all the people of Earth.

The NASA Global Precipitation Measurement (GPM) Core Observatory team is seen during an all-day launch simulation for GPM at the Spacecraft Test and Assembly Building 2 (STA2), Saturday, Feb. 22, 2014, Tanegashima Space Center (TNSC), Tanegashima Island, Japan. Photo Credit: (NASA/Bill Ingalls)

In the control room there’s commotion of a sort, but far, far from the white knuckle derring-do of Hollywood rocket launches. In this rehearsal everyone has their lines down cold, and the consensus is that everyone is hitting their marks on time, on cue. To the non-technical observer there’s a refreshing cool among the corps that instills confidence. Come launch time that confidence and cool will be essential. All participants will have to be on console at launch-minus-10 hours, keeping an eye on every single thing that happens before lift-off. At 30 minutes before launch until 30 minutes after, nobody will enter or leave the control room for any reason whatsoever.

Tim Gruner speaks into a headset, a direct line of communications with the Mission Operations Center at Goddard in Maryland. His voice, along with streams of computer data, flies around the planet to keep all parties on track. It’s nighttime in Maryland during the rehearsal, but during the big show, day and night will be reversed.

Andy Alyward and John Schater have the unusual task of actually standing by at the launch pad. Ostensibly responsible for powering up the GPM Observatory before launch, they’re only on site in case of a problem with the automated computer scripts. At launch-minus-10 hours, they’ll confirm good power, and then high-tail it from the launch site for the safety of control room several miles away. Their oversight is critical because at launch time several systems need to be powered up, including command and data handling, communications receivers, and heaters. Batteries will keep the satellite operational until solar panels unfurl, it tips toward the sun, and starts making its own electricity.

The real action is back at Goddard’s Mission Operations Center and the launch control room located elsewhere at the Tanegashima Space Center. Here in the satellite control room, the group of specialists carefully watching their monitors are largely keeping tabs on their satellite, waiting atop a sleeping Mitsubishi H-IIA heavy lift rocket. Like they say in theater, there’s no such thing as an unimportant role no matter how small. The team here may not be those launching the rocket, but their payload is the big reason this rocket launch matters so very much.

In conversations with the team afterward, the prevailing sentiment is not one of anticipation, but of impending completion. Sure, there’s plenty of excitement, but the NASA team has been in Japan for a long, long time, and home sings its eternally wistful song. There’s nothing like a successful rocket launch to remind you that you just saw a big job through to it’s completion. With this solid rehearsal under their belts, the team is ready to let that moment of completion fly.

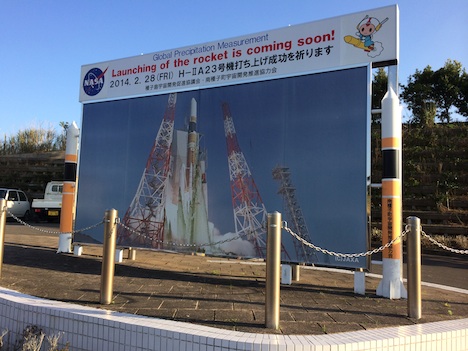

Welcome to Minamitane, Japan. A billboard announcing GPM’s launch on Feb. 28 th (27th in the U.S.) at the nearby Tanegashima Space Center greets visitors as they come into town. Credit: NASA / Ellen Gray

At the town line into Minamitane on Tanegashima Island, Japan, a giant billboard announces, “Global Precipitation Measurement / Launching of the rocket is coming soon!”

Six days to be exact.

I grinned when I saw it. Global Precipitation Measurement, or GPM, is why I’m in town. The launch window begins at 1:07 p.m. Feb. 27 (U.S. EST) / 3:07 a.m. Feb 28 (Japan ST).

I’m Ellen Gray, the science writer for the mission. Over the coming week before launch, video producer Michael Starobin and I will be reporting from the launch site as the GPM team in Japan works with NASA’s mission partners, the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) and Mitsubishi Heavy Industries, on the final preparations before liftoff.

“Global Precipitation Measurement” is a mouthful, but an accurate one. The mission is going to measure all types of precipitation — rain, snow, hail, and that slushy winter mix — across nearly the whole globe, every three hours. When people hear me say that, the question I get is how is one satellite going to do all that? The short answer is that one satellite can’t do it by itself.

The overarching GPM mission consists of more than one satellite. The big picture of global rainfall comes from the combined observations of many rain and weather satellites operated by different countries or agencies. Each satellite has a similar instrument that measures precipitation, and all that data combined is what gives you the global picture.

The GPM Core Observatory — the satellite launching next Thursday — is going to pull all the measurements from the different satellites together into a single data set. Observations from its radiometer will act as the standard to unify all the other satellite measurements. The Core Observatory’s second instrument is a radar, and together with the radiometer, scientists won’t just be seeing where it’s raining, they’ll be able to study how raindrops and ice particles behave within clouds, and ultimately Earth’s water cycle, in detail they couldn’t before. And it’s the first precipitation mission designed to send back measurements of light rain and snow, two of the trickiest types of precipitation to measure from space.

[youtube RlFFpzfXwYc]

Stay tuned for a busy week from Tanegashima. You can find the latest mission updates, stories and videos at http://www.nasa.gov/gpm. For photos, Bill Ingalls (@nasahqphoto) will be posting daily to the GPM Mission Set at NASA HQ Flickr. You can also follow the mission on twitter @NASA_Rain and on Facebook. For more in depth information on the GPM mission, Earth Matters put together a nice primer of videos and links. And, of course, we’ll be blogging right here under GPM in Japan, the Road to Launch.

Live coverage of launch will begin at 12:00 p.m. Feb 27 (EST) on NASA TV and online at: http://www.nasa.gov/ntv

Flyers at the Sun Pearl Hotel announcing Thanksgiving dinner for Saturday Nov. 30, 2013. Credit: NASA / Michael Starobin

The kitchen of the Sun Pearl hotel doesn’t have an oven. Most Japanese kitchen’s don’t, in fact, but Saturday morning, Nov. 30, the borrowed kitchen was in full swing. Cody Buell, systems administrator for the Global Precipitation Measurement mission’s team in Japan, chopped mushrooms that would go into the stuffing that Courtney Buell was stirring together on the stove. Yumiko Seki, an engineer for Mitsubishi Heavy Industries responsible for launch services for the Japan Aerospace and Exploration Agency, chopped garlic and onions at another counter. Meanwhile Suja Lee, the GPM support staff interpreter, put together the sauce for Korean barbecue in case the menu of mashed potatoes, mashed sweet potatoes and green bean casserole wasn’t enough.

As for the four turkeys, Courtney told me, Lou Nagao on the Ground Support Equipment team, had arranged for them, and she didn’t know where they were coming from. They were just going to show up by three.

Courtney Buell and Yumiko Seki at work in the kitchen of the Sun Pearl Hotel. Credit: NASA / Ellen Gray

The third Thursday of November in Japan is just another Thursday. In the GPM clean room, Thanksgiving day was busy as the mechanical team moved the spacecraft from its traveling L-frame to the Aronson table, which supports and rotates the spacecraft as needed for the inspections that followed. So Thanksgiving dinner was moved to Saturday when most of the team had downtime. (On the schedule were solar array inspection and prep work for battery installation.)

Lou wasn’t hard to find. He was in the hotel lobby with Midori Asou, the owner of the Sun Pearl who was opening boxes of Christmas ornaments and putting him to work decorating the small trees set around the entrance. The Sun Pearl lobby was already a riot of decorations, most of them space related. Models of Japanese rockets stand on the reception desk, and a stuffed HII-A, GPM’s launch vehicle, hangs from the overhang with the GPM water cycle card hanging below. On the far wall are more than a dozen mission stickers, including one for GPM, one for its predecessor mission the Tropical Rainfall Measuring Mission, and one for GCOM-W1, a JAXA rain and climate mission that will contribute data to the GPM mission’s global data products.

The Sun Pearl is one of the hotels that the GPM team has been staying at for years, as various team members have come for launch site visits and meetings with their JAXA and Mitsubishi counterparts. It’s family-run and feels as quirky as any bed-and-breakfast. Lou joked with Midori-san as she told him which set of ornaments go with which tree. Her English isn’t strong and, despite having Japanese parents, Lou’s Japanese isn’t strong either, but it didn’t matter — they were getting along just fine.

Midori Asou, one of the owners of the Sun Pearl Hotel, pretending to eat a fake holly berry while she decorates a Christmas tree. Credit: NASA / Ellen Gray

Midori-san was one of the big reasons we were having Thanksgiving at all, Lou told me. She helped Courtney, Cody, and Suja find ingredients for an American meal, helping them navigate the small town grocers. She recruited a few of her friends with ovens to bake apple pie, and she opened up her kitchen to the cooks.

As for the four turkeys, yes, Lou had arranged for them. But he didn’t know where they were coming from either.

Courtney and Cody, the Thanksgiving organizers, had struck out with finding turkeys earlier in the week when Lou heard about their search. He started asking around as well, and one of the people he asked was the owner of the karaoke bar across the street, Emiko’s Club. Karaoke is huge in Japan, and a big hit among the GPM team, too. Once Emiko-san understood what Lou was looking for, she introduced him to another of the karaoke singers at the bar that night, Toshihiko Nakagawa, one of the engineering team leads from Mitsubishi. Nakagawa-san said he would see if he could help and on Tuesday asked Lou how many turkeys they needed.

Mitsubishi Heavy Industries is the primary contractor for JAXA at Tanegashima Space Center. They manage most of the operations including launch preparations and assembling the rocket. They are the team on the ground that works closest with the GPM engineering team. But most of the GPM team has been at Tanegashima for a relatively short time, and at work, it’s all about the mission. This Thanksgiving dinner was a chance to get to know them as fellow members of the GPM family.

The four turkeys showed up, fully cooked as promised, and at six p.m. so did a long line of hungry Americans and their Japanese guests. Jay Parker, GPM’s mechanical team lead, opened the evening with thanks for our hosts and the crew that put dinner together. He added a special tanks for the Mitsubishi team and their crane operator who performed the very difficult lift of the spacecraft out of the L-frame. Then, paper plates loaded with mashed potatoes and sweet potatoes, green bean casserole, turkey, and Korean barbecue from the grill out back, everyone found a seat in the dining room or at one of the extra tables set up in the lobby and dug in — with chopsticks.

The food was delicious, a little bit of home brought across the ocean for a night. Lou introduced me to Emiko-san, and a little later found me again to introduce me to Nakagawa-san and another Mitsubishi engineer. “This is Sakae-san. He got us the turkeys!” said Lou. Sakea Gushima is on Nakagawa-san’s team and when Nakagawa-san mentioned the Americans looking for turkeys, he knew a guy. He has a friend who just took over management of one of the local restaurants and put in the order.

While we chatted, Lou explained what Thanksgiving meant for us. “It’s a time when families come together,” he said. “And if you can’t go home, someone will take you in.”

How do you launch a satellite into space? It isn’t easy. The simple answer would be to build one, place it on a rocket, and shoot it off.

But building and launching satellites turns out to be exceedingly complicated things to do. They’re highly complex machines, requiring profoundly precise levels of craftsmanship, not to mention extraordinary inventiveness. Armies of specialists work closely with supremely skilled designers and mission planners for years to build typical satellites. Most people involved have expensive educations under the belts, and intense, serious years of work proving their mettles while they move up the ranks.

Satellites need money, too–lots and lots. Rockets are expensive; the satellites themselves are expensive; ground operations are expensive.

All of this means huge crowds of people, and in any huge crowd of people you’re going to have differences. People bring different backgrounds, different experiences, different points of view. They disagree; they fall in love; they cause trouble; they stand atop metaphoric mountaintops waving flags like heroes.

Sometimes they sing together, no matter what stripe they wear on their sleeve.

In the small Japanese town of Minimitane on the island of Tanegashima, a small army of NASA engineers worked together in late 2013 to complete the final phases of construction for one of the most sophisticated Earth observing satellites every built. The satellite is called GPM, for Global Precipitation Measurement, and it’s been years in the planning between NASA and the Japanese space agency JAXA.

It’s Thanksgiving weekend, and dozens of these folks are far, far from home. The past week of work has pushed and tested this crew of diverse specialists, and folks know that mistakes at this stage are not easily corrected. With launch just three months away, there’s pressure to operate at high levels of performance. That’s why when Friday night rolled around, promising long flights home for a portion of the team and flights in from replacement players, a big portion of those still on the island met at a local watering hole to unwind. The scene was no different than millions other similar work crews meeting for drinks after longs stretches on the line. And yet….and yet….

The sign for Emico’s Club, one of the karaoke bar’s in Minamitane, Japan. Credit: NASA / Michael Starobin

It happens elsewhere, too, but Japan has a special lock on a peculiar pastime in bars: they sing karaoke. Thirty NASA engineers ordered drinks and started selecting songs.

These engineers are not artists in the traditional sense. As the room’s resident filmmaker, I was decidedly the odd fish in the pond, a koi in a school of tetras. As I got to know the crowd a little bit over the preceding two weeks, I certainly understood how they didn’t necessarily see themselves as artists in the traditional sense, even as I appreciated their craftsmanship and ability to solve tricky problems by looking at them with inventive, disciplined eyes. Often those who work in fields not traditionally regarded as “the arts” miss the opportunity to appreciate shared traits with those who actually do.

Early jokes in the bar began to give way to honest laughter. People began to relax. People took turns singing, poking jibes, having fun. Then the song changed on the karaoke system, and everyone started singing together. We sang The Beatles’s “Let it Be”. Thirty voices rose up together, regardless of political views, sentiments, aesthetic taste, or even deep knowledge of each other. Many in the room didn’t know others there beyond a few cursory greetings throughout the week. But here was a forty year-old song by a British band, easy to sing, resonate of universal things, sung by Americans working on an international space mission on a small Japanese island. We sang from our hearts; people swayed and laughed as they sang, filled glasses between verses, sang louder.

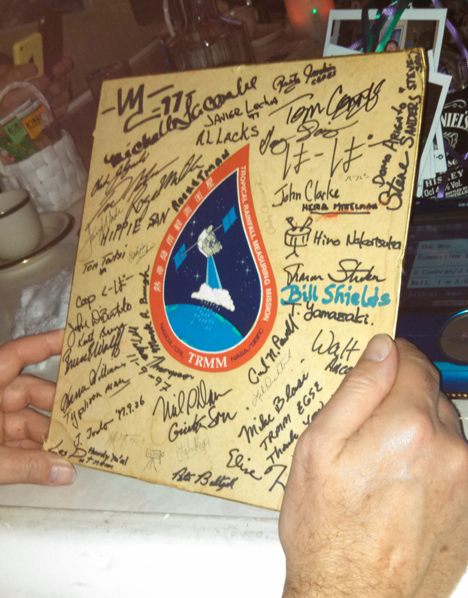

Emico’s has been a popular for after-work karaoke since the Tropical Rainfall Measurement Mission launched from Tanegashima in 1997. Emico, the owner, has a TRMM sticker on a board that’s signed by the TRMM team. She also has Polaroid photos of all her patrons over the years. Credit: NASA / Ellen Gray

In the movies the song would have ended with some sort of deeply satisfied looks among people, one to another, telling the audience of some intimate bond of camaraderie. No so in reality. Bon Jovi followed almost immediately, and no one hesitated to get their New Jersey rocker in gear. The moment passed quickly, and for the rest of the night the Earth spun through space as it always does, and folks in this tiny little bar in Minimitane, Japan acted zany and had enjoyed each other’s company. But I’m not being nostalgic here: I’m certain of something. While singing Let it Be, the room changed, even for just the three minutes it played. For a moment, the nuances of tribal distinctions fell away. We were all together, and that was enough. In fact, it was all anyone needed.

People want to be part of experiences that make them feel connected to other people, want to make them feel greater than the strength of their own individual efforts. For a moment, the group raised their voices, sang “….there will be an answer….let it be…” and smiled at each other, genuinely happy to be alive.

I know I was.

The choreography rivals precision aerial acrobats. The teamwork reflects the forward line of a pro football team. This is the vanguard of NASA’s mechanical engineering corps, and to experience them at their full operational power is to gain a profound appreciation for how much more goes into spaceflight than big, booming rockets.

Mechanical team lead Jay Parker briefs his team on the upcoming lift of the GPM satellite. They’re moving it from the L-frame that kept it safe during transport to the satellite support table that will allow them to rotate the spacecraft for inspection. Credit: NASA / Michael Starobin

Ages range from mid-twenties well into mid-sixties. A handful of women in the ranks reflects a slowly changing demographic, but it’s still mostly a male crew. A visitor may have to look carefully, however. The clean room “bunny” suits everyone must wear has a way of turning human morphology into ambulatory, genderless marshmallows. They’re always funny the first time someone suits up. Then they’re not. Proper clean room garb includes non-static jumpsuits embedded with micro-mesh electro-diffusion wires, designed to insure that even the smallest discharge of static electricity has no chance of damaging delicate circuit boards. Face masks, hair bonnets, rubber gloves, and electrostatically inert booties complete the ensemble. Different missions have levels of “clean”, necessitating nuanced differences in clean room attire, but general speaking, wearers get used to the extra layers in no time.

The mechanical team handles physical aspects of satellite readiness. How do you move the delicate Global Precipitation Measurement satellite around the globe? That’s mechanical’s job.

The mechanical team has only a few inches of clearance between the L-frame and the satellite. Credit: NASA / Michael Starobin

Wrenches and muscle power come into play, of course, but the mechanical team needs to be knowledgable about a range of disciplines. Working closely with electrical engineers, environmental specialists, satellite designers and more, seemingly simple decisions go through rigorous analysis and consideration before they’re implemented lest unintended down-stream consequences accrue.

That is, of course, the plan. When things come down to old fashioned common sense, this is the team you want to have.

Standing next to Mechanical Team Lead Jay Parker, I watch as the crew prepares to extract the satellite from its L-frame, the mounting skeleton in which it travelled around the world in its shipping box. “See this?” he says. “There’s only three inches of clearance between the satellite and the frame. We can’t just lift it up and out. Too tight.” The massive overhead crane can handle the weight, but the problem is a risk that part of the fragile solar array scrapes the structural girders of the frame.

He tells me the plan is to simply release the satellite from its mounting base, and slide it out of the frame horizontally. To the question about how his guys plan to keep the satellite inside its narrow safety envelope, he deadpans, “Very carefully.” The technique involves little more than horse sense, patience, superb teamwork, and a sculptor’s gaze before striking chisel to stone: they’re going to eyeball the situation and simply make sure the satellite doesn’t swing where it shouldn’t.

The GPM satellite is moved by crane across the clean room to the Aronson table which will support the satellite while the GPM team does its final preparations and testing before launch. Credit: NASA / Micheal Starobin

Twenty-minutes later the satellite hangs in space, suspended from high-tension cables. Free of its shipping skeleton, the team begins moving it slowly across the vast integration facility where it will be attached to a special articulating table. Centimeter by centimeter, the bunny suited experts make these moves look easy. On the way to space, these stately, precision maneuvers on the ground matter just as much as lighting the main engines.