In December 2012, NOAA and NASA released a new map of the Earth at night. Built with data from the Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) on the Suomi NPP satellite, this revision to the iconic “night lights†map offered better clarity and resolution than ever before, and much more sensitivity to light.

Among the surprises turned up by the new map, VIIRS found something fishy off the coast of Argentina. About 300 to 500 kilometers (200 to 300 miles) offshore, a city of light appeared in the middle of the South Atlantic Ocean (image above). There are no human settlements there, nor fires or gas wells. But there are an awful lot of fishing boats.

Adorned with lights for night fishing, the boats cluster along invisible borders: the edge of the continental shelf, the nutrient-rich Malvinas Current, and the boundaries of the exclusive economic zones of Argentina and the Falkland Islands. The night fishermen are hunting for Illex argentinus, a species of short-finned squid that forms the second largest squid fishery on the planet.

The fishery is fueled by abundant nutrients and plankton carried on the Malvinas Current. Spun off of the Circumpolar Current of the Southern Ocean, the Malvinas flows north and east along the South American coast. The waters are enriched by iron and other nutrients from Antarctica and Patagonia, and they are made even richer by the interaction of ocean currents along the shelfbreak front, where the continental shelf slopes down to the deep ocean abyssal plain.

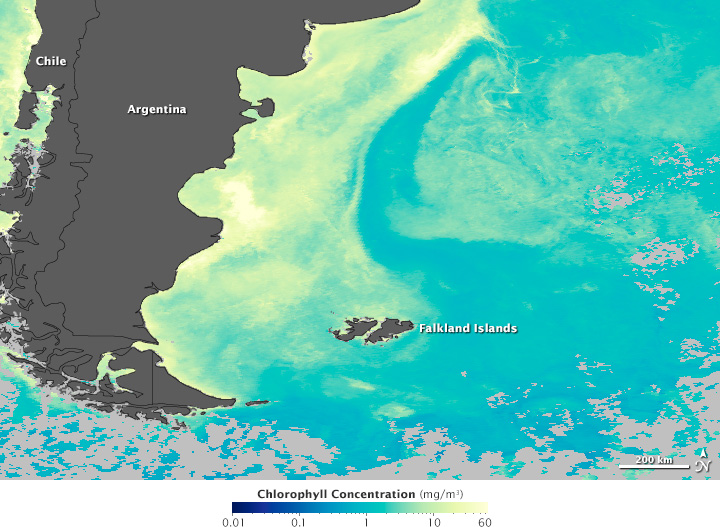

The map above shows the distribution of chlorophyll in March 2012 along the coast of South America. The amount of chlorophyll is a measure of how much phytoplankton is growing near the sea surface. Brighter yellows show the areas with the highest concentrations; blues and greens have low concentrations of chlorophyll.

“Squid aggregate in high concentrations at the shelfbreak because it is a very productive area during austral spring and summer,” said Marina Marrari, a biological oceanographer with Argentina’s Servicio de Hidrografia Naval (Hydrographic Service). At the shelfbreak front, microscopic plant-like organisms—phytoplankton—explode in population in various seasons. This grass of the sea feeds zooplankton and fish, which then become food for Illex argentinus and other marine creatures.

Working in these high chlorophyll areas, fishermen light up the ocean with powerful lamps that attract the plankton and fish species that the squid feed on. The squid follow their prey toward the surface, where they are easier for fishermen to catch with jigging lines. The images below show the locations of fishing boats on nine consecutive nights from April 17 to 25, 2012. Lights appear sharper on some nights and more diffuse on others due to the presence or absence of cloud cover and fog.

In the South Atlantic, Argentine and Falklands citizens have exclusive rights to fish out to 320 kilometers (200 miles). As the images suggest, ships from other nations work as close to that border as they can to get a share of the squid fishing.

“The satellite images are a tool to understand what is happening with the fishery, especially in international waters,” said Ezequiel Cozzolino of El Instituto Nacional de Investigación y Desarrollo Pesquero (Argentina’s national fisheries research institute). “The images allow us to estimate the number of foreign jigging fleets that are fishing Illex argentinus, and to calculate the weekly captures of the species.”

Read more about this night lights story in our new feature: Something Fishy in the Atlantic Night.

NASA Earth Observatory image by Jesse Allen and Robert Simmon, using Suomi NPP VIIRS data provided courtesy of Chris Elvidge (NOAA National Geophysical Data Center). Suomi NPP is the result of a partnership between NASA, NOAA, and the Department of Defense. Caption by Mike Carlowicz.