In March 2012, the Sun unleashed the most intense radiation storm since 2003, peppering satellites with charged particles and igniting strong auroras around both poles. A group of high school students in Bishop, California, knew just what to do: They launched a rubber chicken.

The students inflated a helium balloon and used it to send “Camilla” to an altitude of 120,000 feet (36.5 kilometers), where she was exposed to high-energy solar protons. “We equipped Camilla with sensors to measure the radiation,” said Sam Johnson, age 16, of Bishop Union High School’s Earth to Sky student group. “At the apex of our flight, the payload was above 99 percent of Earth’s atmosphere.”

Launching a rubber chicken into a solar storm might sound strange, but the students had a reason: They are doing an astrobiology project. “Later this year, we plan to launch a species of microbes to find out if they can live at the edge of space,” said team member Rachel Molina, age 17. “This was a reconnaissance flight.”

Many space enthusiasts are already familiar with Camilla, the mascot of NASA’s Solar Dynamics Observatory. With help from her keeper, Romeo Durscher of Stanford University, Camilla corresponds with more than 20,000 followers on Twitter, Facebook, and Google+ about the latest results from NASA’s heliophysics missions.

Camilla actually flew twice: once on March 3, before the radiation storm, and again on March 10, while the storm was raging. On the outside of her space suit—knitted by Cynthia Coer Butcher from Blue Springs, Missouri—Camilla wore a pair of radiation badges, the same kind worn by medical technicians and nuclear workers to assess their dosages.

On March 3, the Earth to Sky team and a local class of fifth graders attached Camilla to the payload, a modified department store lunchbox full of instruments. The payload included four cameras, a cryogenic thermometer, and two GPS trackers. Seven insects and two-dozen sunflower seeds (Helianthus annuus) were also sent up to test their response to near-space travel.

The students adjusted the payload and parachute, inflated the balloon, and released the “stack” into a cloudless blue sky just before local noon. "It was a beautiful lift-off," says Amelia Koske-Phillips, age 15, the team's payload manager and launch boss.

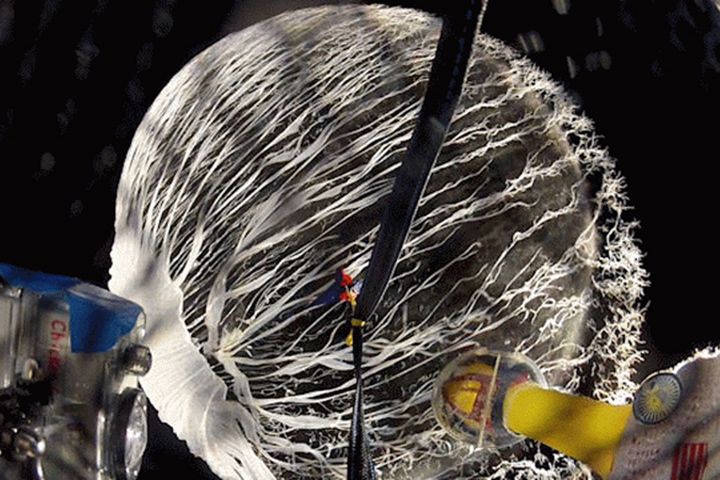

During the two-and-a-half-hour flight, Camilla spent approximately 90 minutes in the stratosphere, where temperatures (-40 to -60C) and air pressures (1 percent of sea level) are akin to those on Mars. The balloon popped (lower photo) at an altitude of 36.5 kilometers (22 miles), and Camilla parachuted safely back to Earth. The entire payload was recovered intact from a landing site in the Inyo Mountains.

One week later, on March 10, 2012, with a solar storm underway, the students repeated the experiment and Camilla flew into one of the strongest proton storms in years. Sparked by activity in sunspot AR1429, the Sun unleashed more than 50 solar flares during the first two weeks of March. At the peak of the storm from March 7–10, the charged particles hitting Earth's upper atmosphere deposited enough energy to power New York City for two years. At the moment of Camilla's launch on March 10, Earth-orbiting satellites reported solar proton counts at approximately 30,000 times normal.

The fifth grade assistants are now planting the sunflower seeds to see if radiated seeds produce flowers that are different than those grown from the seeds that stayed on Earth. They're also pinning the corpses of the insects—none survived—to a black “Foamboard of Death,” a rare collection of bugs that have been to the edge of space.

Meanwhile, Camilla’s radiation badges have been sent to a commercial laboratory for analysis. The students say they are looking forward to reviewing the data and perhaps sending Camilla back for more.

Click here to view a movie of Camilla’s flight.

Photo courtesy of Science@NASA (top) and Earth to Sky, Bishop California (lower). Caption by Tony Phillips, Science@NASA.