|

|

|||

|

Devastating drought has returned to the heart of Dust Bowl country. On the High Plains of northeastern New Mexico, southeastern Colorado, southwestern Kansas, the Oklahoma Panhandle, and northern Texas, drought has been creeping up since fall 2007. By mid-June 2008, the Oklahoma Panhandle and surrounding areas slid into “exceptional drought,” the most severe category of drought classified by the U.S. National Drought Mitigation Center. |

|||

|

Cimarron County, Oklahoma, the westernmost county in the state, is “at the epicenter of the drought,” according to staff climatologist Gary McManus with the Oklahoma Climatological Survey (OCS). The land is occupied by wheat farms, corn fields, and pasture. It’s an area of periodic drought; the Dust Bowl years have not yet faded from living memory. |

In the first half of 2008, an exceptional drought descended on the High Plains, centered on Cimarron County, Oklahoma. This map shows the extent of drought in the continental United States on July 22, 2008. (Map by Robert Simmon, based on data from the U.S. Drought Monitor.) |

||

|

|||

|

“The area has been in and out of drought since the start of the decade. Mostly in,” McManus said. “But fall of last year was when it really started to get bad. In some places, this year has been as dry or even drier than the Dust Bowl.” As of early August, the Oklahoma panhandle was experiencing its driest year (previous 365 days) since 1921, according to OCS calculations. Through July, year-to-date precipitation in Boise City, Cimarron’s County Seat, was only about 4.8 inches, barely half of average and drier than some years in the 1930s, the height of the Dust Bowl. |

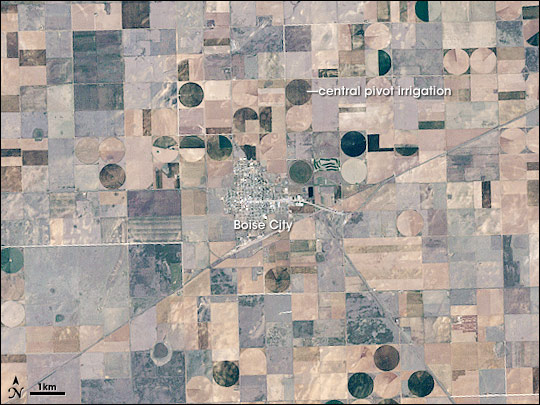

Boise City, in the center of Cimarron County, is surrounded by a semi-arid landscape typical of the Oklahoma Panhandle. Square and rectangular fields, some fallow, are mixed with circular ones that are watered by central pivot irrigation. This image was captured on May 11, 2000, when the area was not in drought. (Image by Robert Simmon, based on Landsat 7 data.) |

||

|

|||

|

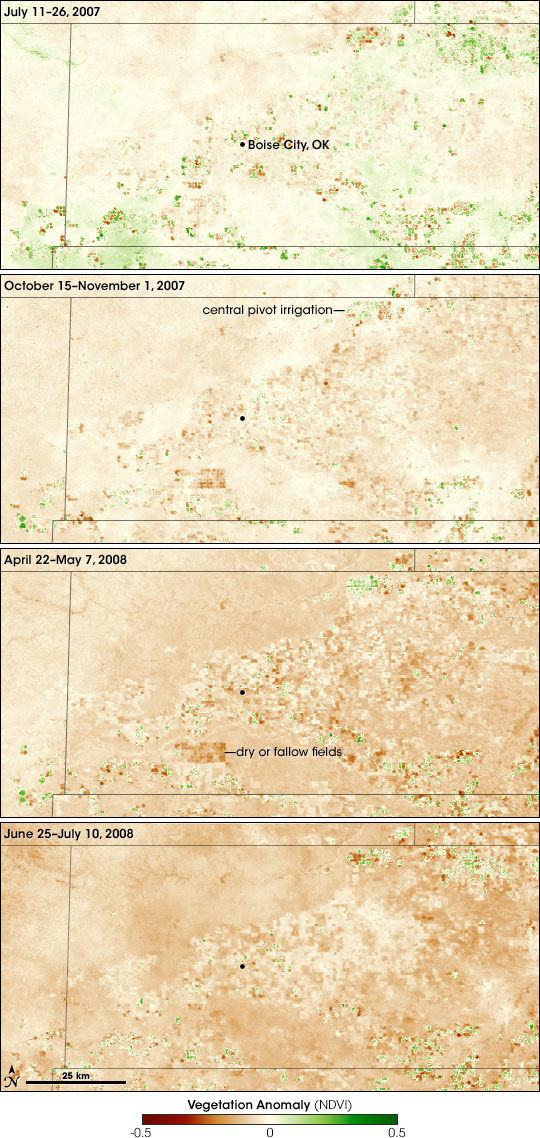

The toll of the drought on crops and pasture is evident in satellite-based vegetation images spanning the past year. On NASA’s Terra satellite, the Moderate Resolution Imaging Spectroradiometer (MODIS) collects observations of visible and infrared light that scientists use to create a scale, or index, of vegetation conditions. In images from late July 2007, conditions appeared near or only a little below normal compared to the 2000-2006 average. In mid-autumn, however, during the beginning of the growing season for the winter wheat crop, conditions had already started to deteriorate. By late April/early May, the impact of the drought on the area’s crops and rangeland was dramatic. In late June and early July, conditions in the agricultural lands appeared to improve somewhat. The apparent improvement could be misleading however. Paul Toon, the Cimarron County Executive Director for the Oklahoma Office of the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s (USDA) Farm Service Agency, says the Panhandle did receive patchy rains in June and July. But late June or July is also when the season’s winter wheat crop is typically harvested. In crop areas, at least, it may be normal for vegetation to be sparse at that time of the year. So the drought might not seem as dramatic in those areas. |

Precipitation in Boise City from January through July 2008 was only 12 centimeters (less than 5 inches), only half of average. The dryness is on par with the worst years of the Dust Bowl decade, which came to be called the “Dirty Thirties.” From 1930 to 1936, the January–July precipitation ranged from 10 to 18 centimeters. (Graph by Robert Simmon, based on data from the Global Historical Climatology Network and NOAA NNDC Climate Data Online.) |

||

|

|||

|

Viewed from the ground, the situation is equally discouraging. According to Cherrie Brown, district conservationist for the USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service in Boise City, subsoil moisture is virtually non-existent. “Any rain that falls is sapped by evaporation in two or three days. Four feet down, there is literally no moisture left in the soil. Recently we were digging as part of a project to decommission a county well, and we dug down to a depth of 7 feet, and there was still no moisture. Even irrigation can’t offset these deficits,” she said. As a result, crops have failed and pasture is severely degraded. |

Vegetation in the Oklahoma Panhandle has declined dramatically since July 2007. These maps show vegetation conditions for several 16-day periods compared to average conditions since 2000. Green indicates more vegetation than normal, brown is less vegetation than normal, and beige indicates that vegetation conditions are average. Grazing land has declined more than many fields, some of which benefit from irrigation. (Maps by Jesse Allen, based on MODIS data from the Global Agricultural Monitoring Project.) |

||

|

|||

|

In places, the land is taking on the look of the Dust Bowl years. In the second decade of the 20th century, settlers to the High Plains plowed up millions of acres of native prairie and began planting winter wheat. The High Plains wheat boom was fueled in part by a global shortages created by the First World War. Near the end of the decade, with wheat prices falling, came one of the area’s regularly occurring droughts. With the prairies gone and wheat fields increasingly fallow, thousands of years of topsoil blew away in black dust storms, earning the decade the name “The Dirty Thirties.” |

A failed crop in a Cimarron County, Oklahoma, wheat field is covered with fine brown sand in June 2008. Without roots to anchor the soil, the ground is prone to severe wind-driven erosion. (Photograph courtesy Gary McManus, Oklahoma Climatological Survey.) |

||

|

|||

|

Since the Dirty Thirties, says Brown, many farmers in the area have committed to soil conservation efforts like “no till” agriculture, in which crop residue is left on fields to anchor soil in place. And while these efforts have gone a long way toward preventing another Dust Bowl, she says, there are places where the ground is starting to blow, just like it did back then. In fields where crops failed, winds have scoured the earth, scraping the soil down to hardpan. Other fields and pasture are being buried by the shifting, sandy soil. |

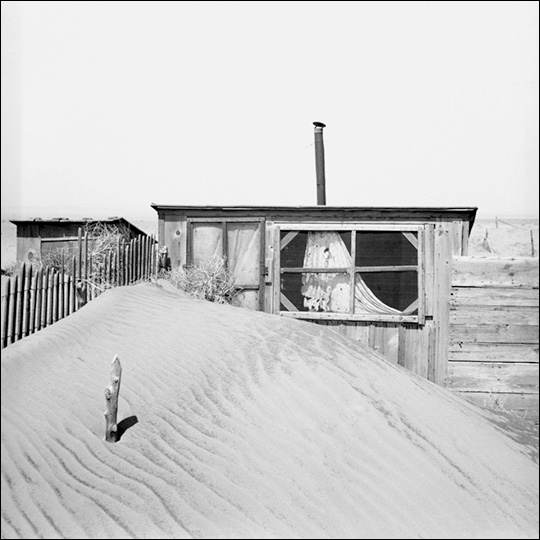

During the Dust Bowl, exceptional drought and farming practices suited to wetter climates turned parts of the High Plains into a near-desert of shifting sand dunes. Thousands of homesteaders were forced off their farms. Wind-blown sand partially covers an outhouse in this photograph taken by Arthur Rothstein in April 1936. (Photograph from the Library of Congress Farm Security Administration-Office of War Information Collection.) |

||

|

|||

|

Kiley Whited, the Natural Resources Conservation Service’s Rangeland Management Specialist for Cimarron County, says the situation on the area’s rangelands may be even worse. On the prairies that once sustained America bison by the millions, even the buffalo grass, whose fibrous root system helps hold the top soil in place, is dying or has gone dormant unusually early. “Buffalo grass is the most resilient of the native grasses to drought and grazing,” says Whited. “To see it wilting and dying is scary.” Because the vegetation has the additional pressure of grazing, it can take longer to recover from drought. |

In summer 2008, drought conditions resemble those of the Dust Bowl: the topsoil on some fields has completely blown away, exposing hardpan. The scoured surface resembles sandstone. (Photograph courtesy Gary McManus, Oklahoma Climatological Survey.) |

||

|

|||

|

To take some of the pressure off stressed rangeland, Cimarron and many other High Plains counties petitioned the Department of Agriculture to release some of the county’s holdings in the Conservation Reserve Program. The program pays “rent” to farmers to keep easily damaged agricultural land fallow. Farmers sign 10-15-year contracts, and they must pay fees and return rent payments to have their land released early. In Cimarron County, says Toon, 30 percent of the agricultural land is part of the Conservation Reserve Program. In emergencies, the USDA can waive fees and let farmers out of their contracts. Farmers can also receive permission for emergency haying and grazing on program lands, but their rent payments are reduced. On August 1, the USDA announced plans to allow emergency grazing and haying on conservation reserve lands in the drought-stricken counties of the High Plains, and said that rental payments to farmers would only be reduced by 10 percent instead of the standard 25 percent cut. In addition, the federal government declared nine counties in western Oklahoma “primary natural disaster areas.” Sixty-six bordering counties in Colorado, Kansas, Missouri, Arkansas, Texas, and New Mexico are eligible for disaster relief under the declaration, which makes low-interest emergency loans available to farmers and ranchers. The declaration may also allow tax breaks for ranchers who have been forced to sell their herds. A farmer herself, Brown describes the Cimarron County residents as tenacious. They are accustomed to the High Plains’ climate extremes, and they have worked hard to avoid making the same mistakes with the land that farmers did at the beginning of the past century. “People aren’t complaining,” says Brown, “they are just trying hard to stay on their land.” But despite conservation efforts that have prevented another dust bowl-like disaster, she says, they are still at the mercy of the climate. “We can’t just go to the store and buy rain.”

|

With the added pressure of grazing, rangeland often suffers more than crop land during droughts. Even buffalo grass, one of the hardiest grasses on the Southern Plains, is dead or dying on some rangeland in Cimarron County, OK. In the background, winds have blown sandy soil into a pile, smothering the prairie. (Photograph courtesy Gary McManus, Oklahoma Climatological Survey.) |

||